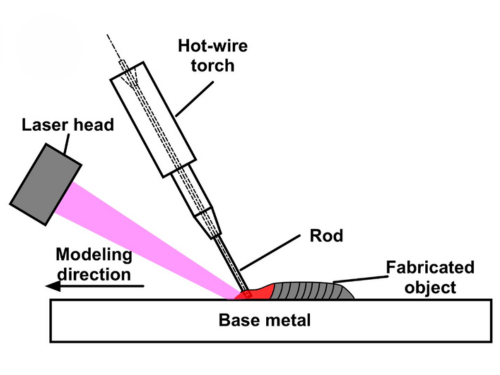

Wedoany.com Report on Feb 10th, Tribology, as the discipline studying friction, wear, and lubrication, holds a significant position in machining performance prediction. Tool wear is directly related to machining costs. The machining process is essentially the interaction between the cutting edge and the workpiece material, where the workpiece material is removed in the form of chips to obtain the desired part shape. Under conditions of high temperature, high pressure, and high-speed material removal, understanding the tribological characteristics at the tool-workpiece interface is crucial for the successful production of discrete parts. Key factors include the friction generated at the tool-chip interface and the naturally occurring tool wear, both of which need to be effectively managed to achieve high material removal rates and low-cost production.

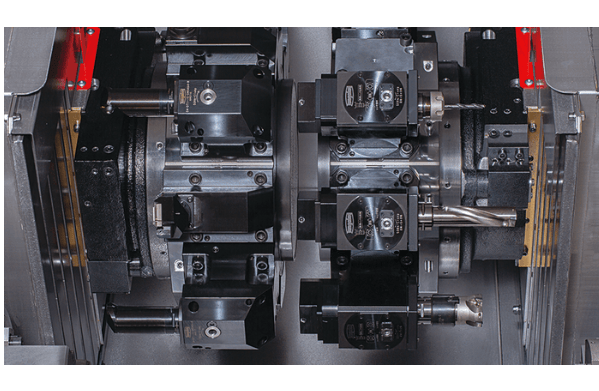

Machining tribology involves the comprehensive consideration of multiple parameters, including machining parameters such as chip width, thickness, and cutting speed, which are determined by depth of cut, feed rate, and spindle speed. Tool material and coating selections are diverse, covering single-layer and multi-layer coating options. Tool geometry parameters include side rake angle, clearance angle, and cutting edge radius, while workpiece material properties, cutting fluid type, and application methods also influence machining outcomes. Tool path strategies such as climb milling or conventional milling, as well as geometric features like helical entry/exit and constant radial engagement, affect machining time, cutting forces, and tool wear rate.

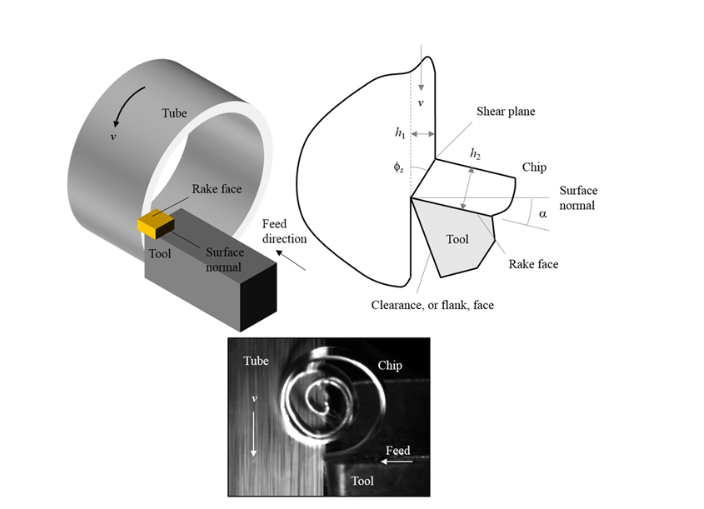

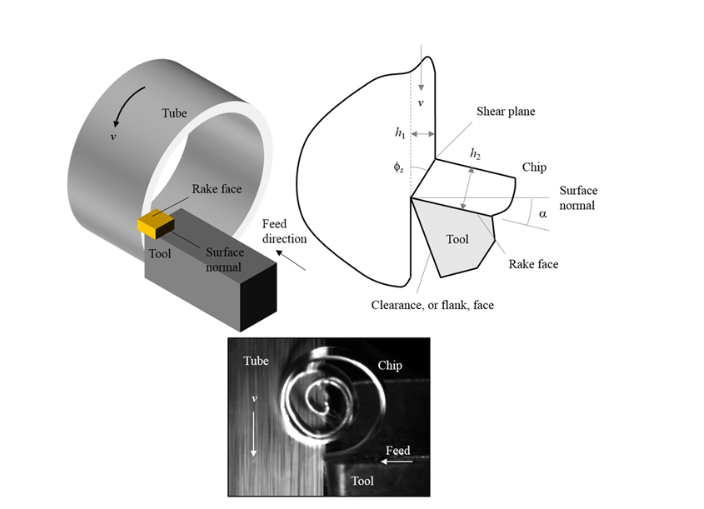

Chip removal characteristics depend on tool geometry, workpiece material, machining parameters, and cutting fluid application. To simplify analysis, the three-dimensional cutting process can be idealized as two-dimensional orthogonal cutting, where strain and forces exist within a single plane. Orthogonal cutting can be visualized as tube turning, with the feed direction along the tube axis. In orthogonal cutting, a sharp tool removes material to form a chip; the uncut material approaches the tool at the cutting speed, and the chip forms along the rake face. Rake angles are categorized as positive, negative, and zero, influencing cutting edge strength and cutting forces. The uncut chip thickness is determined by the feed per revolution in turning and defined by the feed per tooth and tool angle in milling.

Shearing action in orthogonal cutting occurs along the shear plane, with the chip width perpendicular to this plane remaining constant. Utilizing geometric relationships, equations for shear plane length, chip sliding velocity, and required forces can be derived. Cutting force components include the normal force Fn and the tangential force Ft, whose resultant force F deviates from the cutting direction at a specific angle. The friction force Ff acts between the chip and the tool's rake face. Normal and tangential forces are related to the uncut chip area via cutting force coefficients kn and kt. These coefficients are process characteristics dependent on workpiece material, tool geometry, and machining parameters.

The product of force and velocity components gives the machining power. The shear and friction power inputs in metal cutting can lead to significant temperature rises. For example, temperatures in the tool-chip region for steel typically range between 800°C and 1,200°C, depending on the machining process, cutting speed, and alloy composition. This temperature range is below the melting temperature of steel but sufficient to affect material properties. For intuitive understanding, volcanic lava temperatures also range between 800°C and 1,200°C, while candle flame temperatures vary from 800°C in the blue region to 1,400°C at the white tip. These comparisons help visualize the high-temperature environment in machining.