A study from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden has identified significant shortcomings in the EU's hydrogen infrastructure regulations. As the EU pushes forward with hydrogen infrastructure development, requiring all member states to deploy refuelling stations according to uniform principles, these rules may create serious problems.

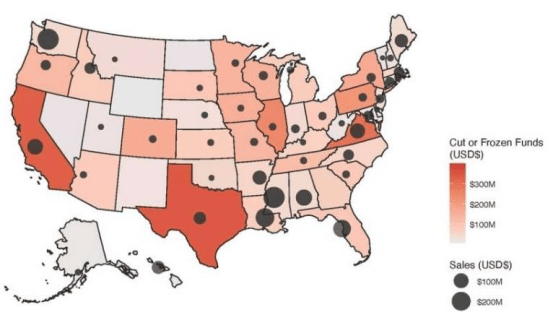

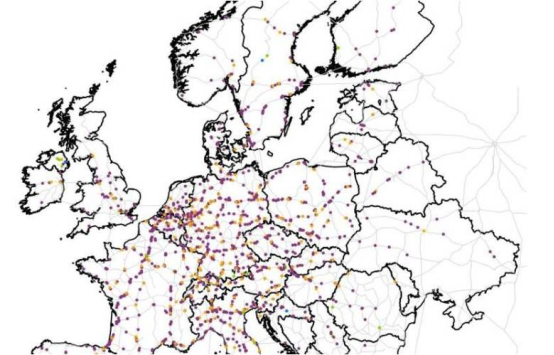

Under the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR), which entered into force in 2023, EU countries must build a hydrogen refuelling station at least every 200km along major roads by 2030, with one in every urban node, to promote hydrogen-powered transport. However, Chalmers researchers, using data from 600,000 freight routes across Europe, found that these requirements often fail to reflect actual demand.

The study, titled "Geospatial Distribution of Hydrogen Demand and Refuelling Infrastructure for Long-Haul Trucks in Europe," was published in the International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. By simulating hydrogen-powered long-haul truck operations in 2050, the researchers discovered a clear mismatch between high-demand locations and current EU rules. Some countries could lose tens of millions of euros annually as a result. For example, France will need seven times more refuelling capacity in 2050 than required by the EU in 2030. Meanwhile, countries like Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece — due to differing traffic volumes — will be forced to build underutilized infrastructure, wasting tens of millions of euros each year in investment and operating costs.

Beyond traffic volume and distance, the study incorporated terrain data from the European Space Agency and found that geography has a much greater impact on energy demand than previously thought. Including parameters such as slope and speed significantly altered energy demand curves, enabling far more accurate determination of optimal infrastructure locations.

The research focused on long-haul transport exceeding 360km, as shorter distances are expected to be covered by battery-electric trucks in the future. The researchers note that numerous studies show batteries are suitable for short ranges, while long distances will require hydrogen or other alternative fuels.

The model not only addresses 2030 demand but also analyzes the long-term sustainability of hydrogen infrastructure investments. The findings have already been used in political discussions on hydrogen infrastructure planning in Sweden and the EU. At the EU level, the researchers have provided input for the 2026 AFIR review, hoping future legislation will better account for national differences. In Sweden, AFIR is seen as a good starting point, but investing in new technology carries risks — this study helps build an economically sustainable hydrogen refuelling network and accelerate the market for heavy-duty hydrogen vehicles.

The research was conducted within the TechForH2 framework — a multidisciplinary centre of excellence for hydrogen research led by Chalmers University of Technology — aimed at developing new hydrogen propulsion technologies for heavy vehicles and forming part of a broader project analyzing the systemic impact of transitioning transport to hydrogen.