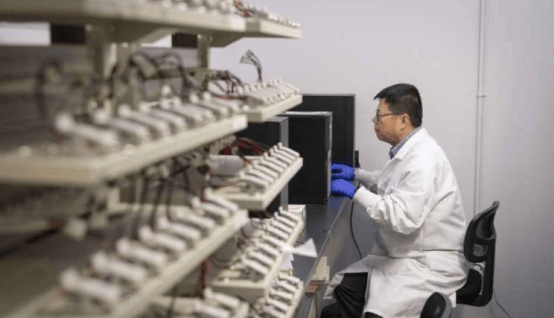

Amid the growing energy consumption of artificial intelligence, a research team at the University at Buffalo has drawn inspiration from the efficient mechanisms of the human brain to develop an innovative neuromorphic computing architecture, poised to bring disruptive changes to green manufacturing and the AI field.

Sambandamurthy Ganapathy, PhD, professor of physics and associate dean for research in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University at Buffalo, noted, "The brain evolved to maximize information storage and processing while minimizing energy use—a capability far superior to any biological system." Although fully replicating the brain's complexity is unrealistic, mimicking its information processing patterns can create more energy-efficient computers, thereby advancing the green development of AI.

The concept of neuromorphic computing originated in the 1980s, but its importance has surged with the explosive demand for computing power and energy in AI tasks. The Ganapathy team focuses on hardware innovation, integrating quantum science and engineering to explore the unique electrical properties of materials suitable for building neuromorphic chips. Graduate student Nitin Kumar explained, "Traditional computers rely on a binary framework, while neuromorphic computing aims to break through this limitation, approaching the complexity of natural systems."

The brain's efficiency stems from the simultaneous storage and processing of information, whereas traditional computers incur high energy costs due to the separation of these functions, leading to extensive data transfer. The Ganapathy team employs "in-memory computing" technology, tightly integrating memory and processors within the chip to significantly reduce energy consumption. This innovation lays the foundation for high-energy-efficiency computing architectures that support AI models.

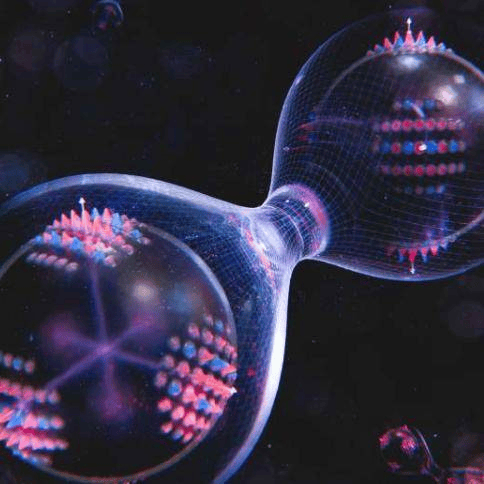

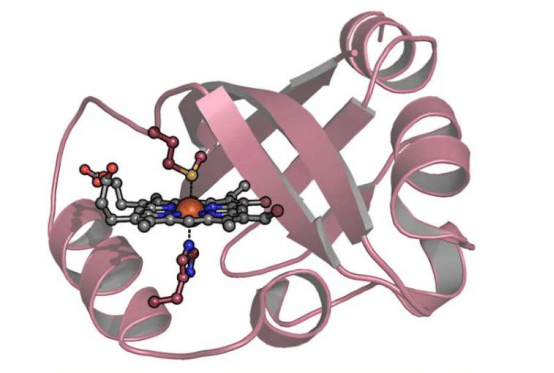

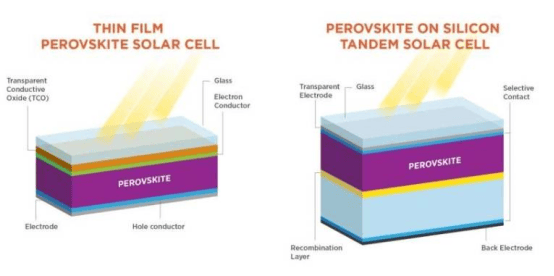

The team is developing artificial neurons and synapses to replicate the electrical signal transmission patterns in biological organisms. Kumar stated, "We aim to achieve synchronized electrical oscillations observed in brain scans, which requires advanced materials with precise control over electrical conductivity." Phase-change materials (PCM) are ideal candidates due to their ability to switch between conductive and resistive phases while retaining "memory" properties. These materials can gradually alter conductivity with repeated electrical pulses, simulating the strengthening mechanism of biological synapses.

The team recently published findings in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, Advanced Electronic Materials, and on the arXiv platform, highlighting the potential of compounds such as copper vanadium oxide bronze, niobium oxide, and metal-organic frameworks. By regulating material conductivity through voltage and temperature, the team delved into their electronic properties. Currently, the team is collaborating with partners to achieve atomic-level control of material structures for precise tuning of electrical switching characteristics.

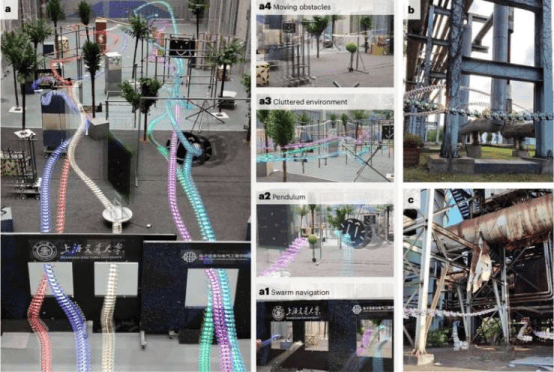

Professor Ganapathy revealed that the next step is to synchronize oscillations across multiple devices, constructing oscillatory neural networks capable of simulating complex brain functions (such as pattern recognition and motor control). He emphasized that neuromorphic computers aim to replicate the brain's functional behaviors rather than consciousness, solving problems in a manner closer to human thinking—nonlinear and highly adaptive, particularly adept at handling limited or ambiguous data.

Neuromorphic chips hold immense potential in autonomous driving. For instance, in sudden road conditions (such as a deer leaping in front of the vehicle), they can make real-time decisions on-device without relying on remote servers. Ganapathy predicted, "Neuromorphic chips may not become ubiquitous in smartphones in the short term but will first land in highly specialized applications, such as real-time response and path planning in autonomous vehicles. In the future, a model of multiple dedicated chips working collaboratively may emerge, rather than a single universal neuromorphic computer."

This research not only provides new ideas for green manufacturing but also opens a new path for the sustainable development of artificial intelligence, marking a key step toward the era of "brain-like computing."