A new study from the University of Colorado Boulder envisions a future where fleets of robots work alongside humans on the lunar surface to build scientific observatories and even habitats. A team of undergraduate and graduate students is tackling the challenge of how humans on Earth can train to operate robots across the Moon's treacherous terrain.

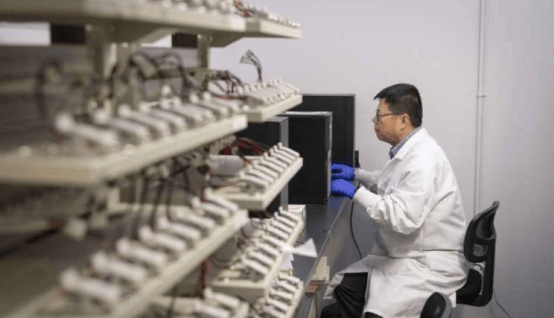

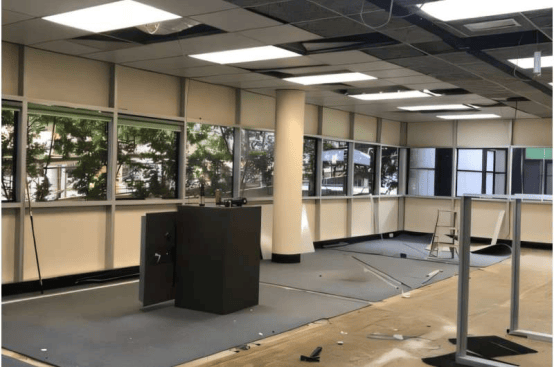

In a windowless, gray-carpeted office on the Boulder campus, a robot nicknamed "Armstrong" is undergoing testing. Team member Xavier O'Keefe wears a VR headset and pilots the robot using cameras mounted on its head. O'Keefe says the first time he controlled it in VR, the immersion felt incredible.

With lunar gravity only about one-sixth of Earth's and the surface riddled with craters—some permanently in shadow—operating robots there is extremely difficult. In a new paper published in Advances in Space Research, O'Keefe, alumna Katie McCartin, and Alexis Muniz report that "digital twins"—hyper-realistic virtual reality environments—can serve as valuable alternative training grounds for lunar exploration, allowing operators to master robot driving without risking millions of dollars in hardware.

The work is part of a larger project led by Jack Burns, professor emeritus of astrophysics and planetary science (APS) and the Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy (CASA). McCartin describes the "Armstrong" robot as a sandbox they can play in to train for all kinds of operations.

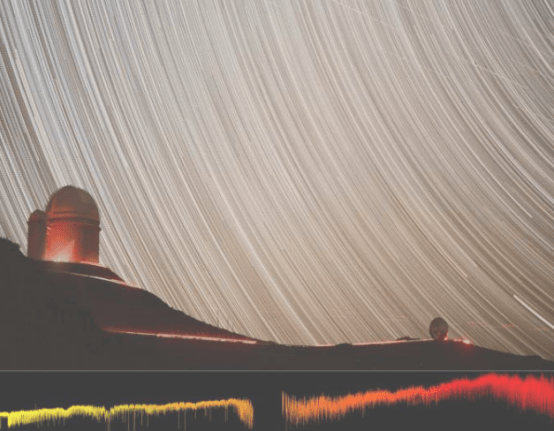

Burns' team is designing FarView, a future lunar observatory consisting of a network of 100,000 antennas covering roughly 77 square miles (117km²) of the Moon's surface. Unlike Apollo, NASA's 21st-century Artemis program will have astronauts and rovers working together. The Boulder effort aims to make lunar robots more efficient and resilient so they maximize the precious time astronauts spend on the surface.

To create Armstrong's digital twin, researchers first used the Unity video game engine to build an exact digital replica of the office—beige walls, monotonous carpet, and all—ensuring the virtual version matched reality as closely as possible.

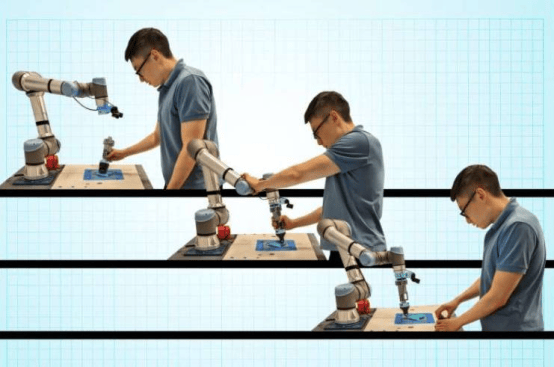

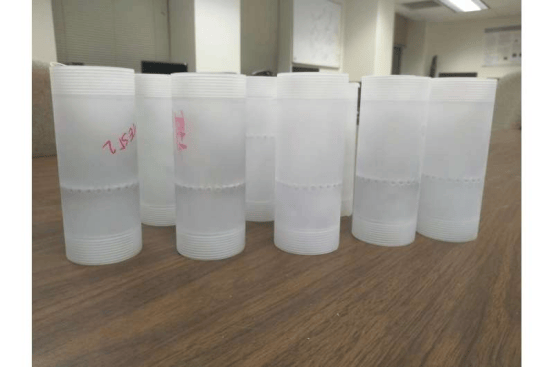

They then ran an experiment: in 2023 and 2024, they recruited 24 human participants to operate Armstrong from inside the room. Half first practiced in the digital office picking up and positioning a plastic block representing a FarView antenna. Those who trained on the digital twin completed the task ~28% faster with the real robot and reported less stress than those who only practiced with the physical machine. O'Keefe says everything in the simulation—from shadows to the texture of the dirt—helps operators train under conditions as close to real as possible, increasing the chances of success once on the Moon.

McCartin says the project gave her and her classmates insight into how real-world research works. One finding: human test subjects consistently made the same mistake—accidentally flipping the mock antenna upside-down when picking it up.

Now Burns' team is moving to the next level, partnering with Colorado-based Lunar Outpost to build digital-twin models of lunar rovers using the same game engine. O'Keefe says the hardest part is getting lunar dust right—rover wheels kick up clouds that can obscure sensors or cameras, and exactly how dust behaves on the Moon is hard to replicate.

Though the research is still campus-based, the team is thrilled to be part of future lunar exploration. O'Keefe reflects: "It's amazing to be involved—even if it's just one small piece of getting humans back to the Moon."