From the ancient Egyptian pyramids to iconic Roman structures, concrete has long symbolised the resilience and ingenuity of civilisation. Yet today, this material that underpins societal prosperity is responsible for up to 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, posing a major challenge to sustainable construction. Recently, designers, materials scientists, and engineers at the University of Pennsylvania have joined forces to combine 3D printing technology with microalgae fossil structures to create a new type of bio-mineral-infused concrete.

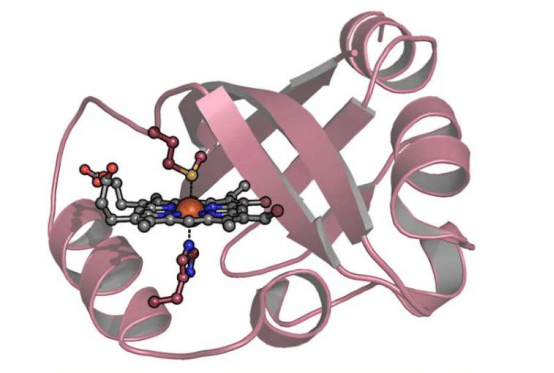

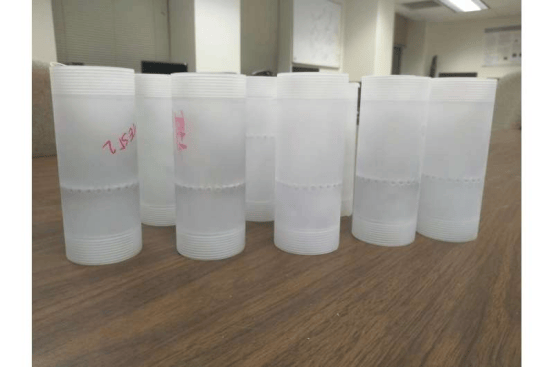

This concrete is lightweight and structurally robust. Compared to traditional concrete, it can absorb up to 142% more carbon dioxide, uses less cement, and still meets standard compressive strength targets. Its key ingredient is diatomaceous earth (DE), a common filler material made from microfossil remains. Its fine, porous, sponge-like texture both improves the stability of the concrete as it passes through a 3D printer nozzle and provides ample space for carbon dioxide capture.

Published in Advanced Functional Materials, the research lays the foundation for building materials that can simultaneously support structures, help restore marine ecosystems, and capture atmospheric carbon. Shu Yang, Professor of Materials Science and Engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science and co-senior author of the paper, noted that normally increasing surface area or porosity reduces strength, but this new concrete does the opposite—its structure actually becomes stronger over time. After optimising the material's geometry, the team achieved "an additional 30% increase in CO₂ conversion rate" while maintaining compressive strength comparable to ordinary concrete.

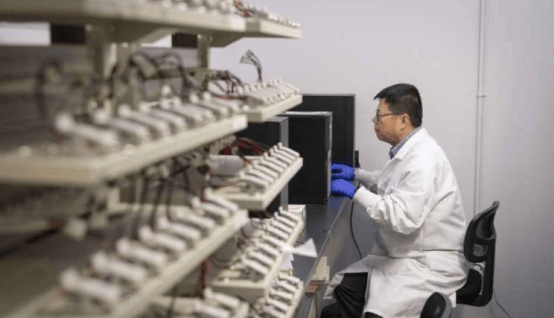

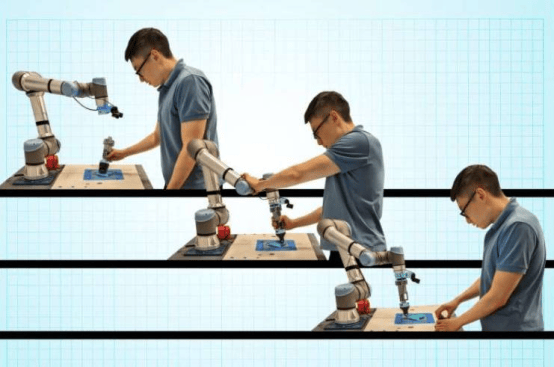

Masoud Akbarzadeh, Associate Professor of Architecture at the Weitzman School of Design and co-senior author, said this opens up a new structural logic, reducing material use by nearly 60% while still bearing loads. Yang initially knew little about concrete but understood that rheology is critical to its behaviour during mixing and printing. Drawing on the expertise of former postdoctoral researcher and first author Kun-Hao Yu, she translated that understanding into a viable 3D-printing solution. Professor Yu described concrete as the ideal challenge, requiring combined chemical, physical, and design thinking.

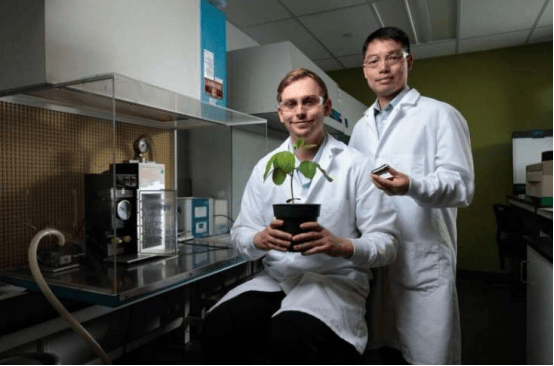

Yang first encountered diatomaceous earth while studying natural photonic crystals and carbon sinks in the Southern Ocean. When diatoms die, they carry carbon dioxide to the seafloor, helping reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Intrigued by this natural material's CO₂-absorbing properties, she began considering its potential incorporation into building materials. The research team discovered that DE's internal pore network provides pathways for CO₂ diffusion, enabling calcium carbonate formation during curing, which increases both CO₂ uptake and mechanical strength.

Yu led the development of printable concrete ink and calibrated the 3D printer variables. Although high porosity normally impedes stress transfer, this material actually becomes stronger after absorbing CO₂. Akbarzadeh and his team employed triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS), a geometry that maximises surface area and geometric stiffness while minimising material usage. They used polyhedral graphic statics to design the concrete structures and combined post-tensioned cables to enhance internal stability. After modelling, the digitally sliced and optimised components were printed and tested: compared to traditional solid concrete blocks, they saved 68% of material, increased surface-area-to-volume ratio by more than 500%, and TPMS cubes retained 90% of the compressive strength of solid cubes while achieving a 32% higher CO₂ uptake per unit of cement.

Looking ahead, the team is advancing the work on multiple fronts, including scaling up to full-size structural elements such as floors, facades, and load-bearing slabs. Akbarzadeh said they are testing larger components with more complex reinforcement schemes, hoping they will be strong, efficient, and buildable at architectural scale. The concrete may also be suitable for marine infrastructure such as artificial reefs, oyster farms, or coral platforms. Yang's group is also exploring synergies between DE and other binder chemistries and considering the possibility of completely eliminating cement or using waste liquids as reactive components. She said that treating concrete as something dynamic—that responds to the environment—will open up an entirely new world of possibilities.