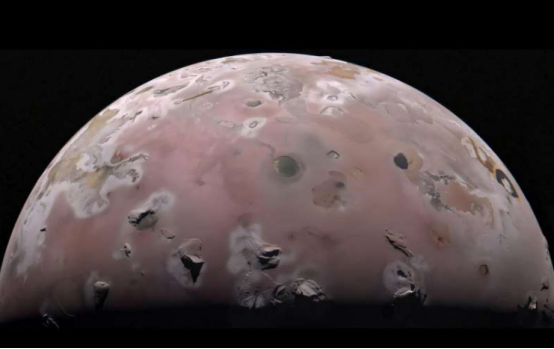

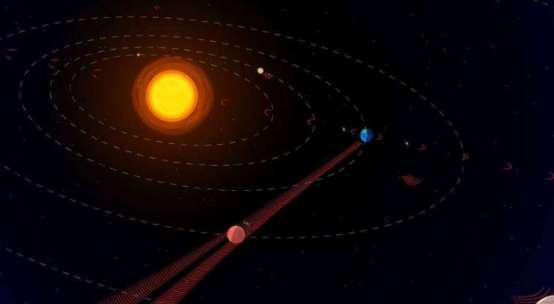

More than 5,000 exoplanets have been discovered beyond our solar system, enabling scientists to explore planetary evolution and contemplate the possibility of extraterrestrial life. Now, a study published in Physical Review D by researchers at the University of California, Riverside, shows that exoplanets (planets orbiting stars outside our solar system) can also serve as tools for studying dark matter.

The researchers investigated how dark matter, which constitutes 85% of the universe's matter, might affect Jupiter-sized exoplanets over long timescales. Their theoretical calculations indicate that dark matter particles could gradually accumulate in the cores of these planets. Although dark matter has never been directly detected in laboratories, physicists are confident of its existence.

“If dark matter particles are sufficiently heavy and do not annihilate, they could eventually collapse into a tiny black hole,” said Mehrdad Phoroutan-Mehr, a graduate student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy and first author of the paper, who worked with Professor Hai-Bo Yu.

“This black hole could then continue to grow, consuming the entire planet and turning it into a black hole with the same mass as the original planet. Such an outcome is only possible under ultra-heavy non-annihilating dark matter models.”

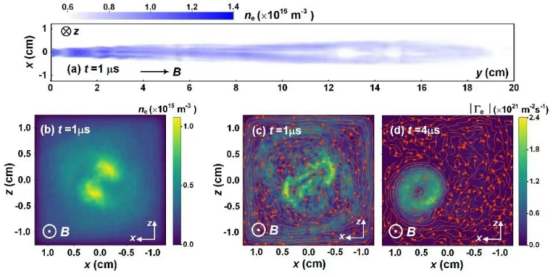

According to the ultra-heavy non-annihilating dark matter model, dark matter particles have extremely large masses and do not destroy each other upon interaction. The researchers focused on this model to demonstrate how ultra-heavy dark matter particles could be captured by exoplanets, lose energy, and drift toward their cores. There, they accumulate and collapse into black holes.

“In gas exoplanets of varying sizes, temperatures, and densities, black holes could form on observable timescales—even multiple black holes within the lifetime of a single exoplanet,” Phoroutan-Mehr said. “These results suggest that exoplanet surveys could be used to search for ultra-heavy dark matter particles, especially in regions presumed to be rich in dark matter, such as the center of our Milky Way galaxy.”

Postdoctoral researcher Tara Fetherolf from the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences also participated in Phoroutan-Mehr’s study.

Phoroutan-Mehr explained that, to date, astronomers have only detected black holes with masses greater than that of the Sun. Most existing theories suggest that black holes must have at least solar-mass scales.

“Discovering a black hole with planetary mass would be a major breakthrough,” he added. “It would support the argument of our paper and offer an alternative explanation to the widely accepted theory that planetary-mass black holes can only form in the early universe.”

Phoroutan-Mehr noted that exoplanets have not been widely used in dark matter research so far, mainly because scientists lacked sufficient data about them.

“But in recent years, our understanding of exoplanets has expanded dramatically, and several upcoming space missions will provide much more detailed observational data,” he said. “As this data continues to grow, exoplanets could be used to test and challenge different dark matter models.”

In the past, scientists studied dark matter by observing objects such as the Sun, neutron stars, and white dwarfs, because different dark matter models affect these objects in distinct ways. For example, some models suggest dark matter can heat neutron stars.

“So if we observe an old and cold neutron star, it might rule out certain dark matter properties, since dark matter is theoretically expected to heat them,” he said.

He added that the fact that many exoplanets (as well as Jupiter in our solar system) have not collapsed into black holes can help scientists rule out or refine dark matter models, such as the ultra-heavy non-annihilating dark matter model.

“If astronomers were to discover a population of planetary-mass black holes, it would provide strong evidence for the ultra-heavy non-annihilating dark matter model,” Phoroutan-Mehr stated. “As we continue to collect more data and study individual planets in greater detail, exoplanets may offer key insights into the nature of dark matter.”

Phoroutan-Mehr pointed out that another possible effect of dark matter on exoplanets (and possibly on planets in our solar system) is that it could cause these planets to heat up or emit high-energy radiation.

“Current instruments are not sensitive enough to detect these signals,” he said, “but future telescopes and space missions might be able to capture them.”

京公网安备 11010802043282号

京公网安备 11010802043282号