Recently, Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), the U.S. Department of Energy’s Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, through a public-private partnership, have developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) method that can more quickly identify the “magnetic shadow” regions in nuclear fusion that protect the vessel from high-temperature plasma attacks—an essential factor for safeguarding the interior of fusion vessels.

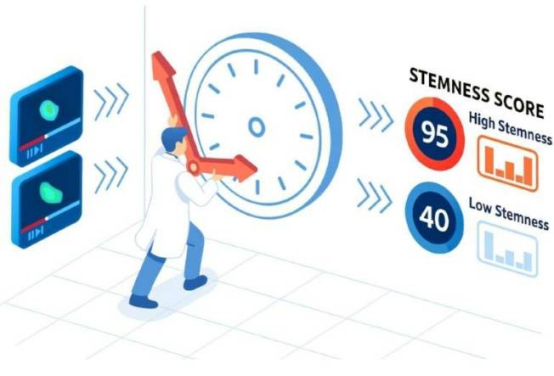

This new AI technology, called HEAT-ML, is expected to lay the foundation for software that can significantly accelerate the design of future fusion systems. Such software can make correct decisions by adjusting the plasma during fusion operations, preventing potential problems in advance. Michael Churchill, co-author of a paper published in the journal Fusion Engineering and Design, stated that this research demonstrates the possibility of using existing code to create AI substitutes, speeding up the acquisition of useful answers and opening new pathways for control and scenario planning.

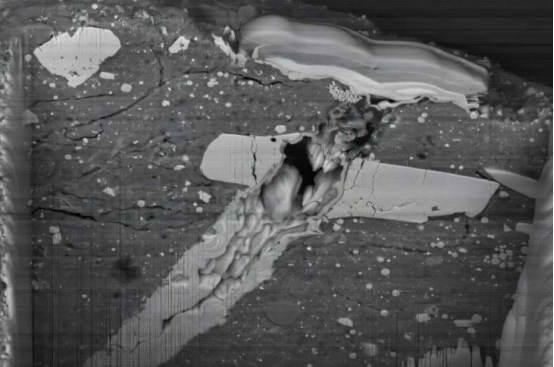

Fusion is the reaction that powers the Sun and stars and holds the promise of providing unlimited electricity on Earth, but researchers must overcome numerous scientific and engineering challenges—one of which is managing the intense heat from plasma. When plasma is confined by magnetic fields in a tokamak fusion vessel, its temperature exceeds that of the Sun’s core. Accelerating computation speed, predicting where heat strikes, and identifying safe regions are key to bringing fusion energy to the grid. Doménica Corona Rivera, PPPL associate research physicist and first author of the HEAT-ML paper, noted that tokamak components facing the plasma can melt or be damaged if exposed to high-temperature plasma, and in the worst case, operations must be halted.

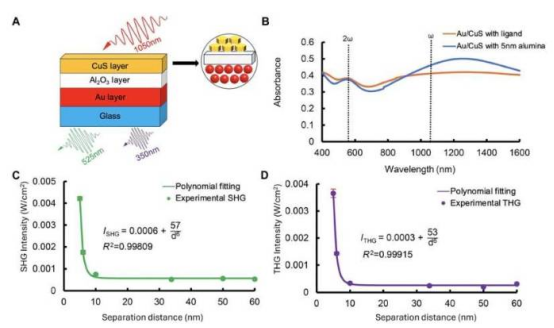

HEAT-ML was specifically developed to simulate a small portion of SPARC (the tokamak device currently under construction by CFS, with the company aiming to achieve net energy gain by 2027). Simulating how heat affects the interior of SPARC is central to achieving the net energy gain goal and represents a massive computational challenge. The team broke down the problem by focusing on the region inside SPARC where plasma heat exhaust is strongest and intersects with the material wall—this area is located near the bottom of the machine, covers 15 tiles, and is the hottest part of the machine’s exhaust system.

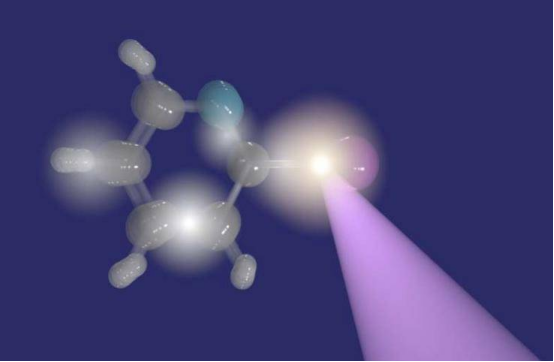

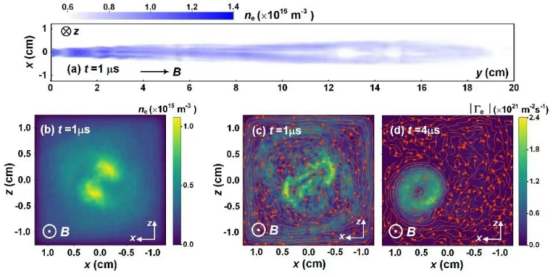

To create the simulations, researchers generated “shadow masks”—3D maps of magnetic shadows. Magnetic shadows are specific areas on the surfaces of internal components in fusion systems that are shielded from direct heat exposure. Their locations depend on the shape of the tokamak’s internal components and their interaction with the magnetic field lines confining the plasma. Initially, the open-source computer program HEAT (Heat Flux Engineering Analysis Toolkit) calculated these shadow masks, but tracing magnetic field lines and finding their intersections with detailed 3D machine geometry was a major bottleneck, with a single simulation taking about 30 minutes—and longer for complex geometries.

HEAT-ML overcomes this bottleneck, reducing computation time to just a few milliseconds. It uses a deep neural network that learns to perform specific tasks through multiple layers of mathematical operations and parameter pattern recognition. The deep neural network was trained on approximately 1,000 SPARC simulation datasets provided by HEAT to learn how to compute shadow masks. Currently, HEAT-ML is specific to the detailed design of SPARC’s exhaust system and applies only to a small portion of the tokamak device as an optional setting in the HEAT code. However, the research team hopes to expand its capabilities to apply shadow mask calculations to exhaust systems of any shape and size, as well as to other plasma-facing components inside tokamak devices.