Asteroid Bennu, the target of NASA's OSIRIS-REx sample-return mission led by the University of Arizona, is a mixture of materials from across the solar system—even from beyond it. Over billions of years, its unique and diverse composition has been altered by interactions with water and the harsh space environment.

These details come from three newly published papers based on analysis of the Bennu samples returned to Earth in 2023 by the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. The OSIRIS-REx sample analysis effort was coordinated by the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory (LPL) at the University of Arizona, with scientists from around the world participating. LPL researchers contributed to all three studies and led two of them.

“This work is something that telescopes cannot do,” said Jessica Barnes, associate professor at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona and co-lead author of one of the publications.

“We can finally say things about this asteroid we've dreamed about for so long, and now that we've finally brought pieces of it back, it's incredibly exciting.”

Bennu is made of fragments from a larger “parent” asteroid that broke apart after a collision with another asteroid, most likely in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

This parent asteroid was itself composed of material from different sources—close to the Sun, far from the Sun, and even from other stars—that came together more than 4 billion years ago during the formation of the solar system.

These findings are the subject of one paper published in Nature Astronomy, co-led by Barnes and Ann Nguyen with NASA's Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division at Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Barnes said: “Bennu's parent asteroid may have formed in the outer solar system, possibly beyond the giant planets Jupiter and Saturn.”

“We think this parent body was hit by an incoming asteroid and shattered. Then the pieces reassembled—and that may have happened several times.”

By analyzing the samples returned by OSIRIS-REx, Barnes and her colleagues obtained the most comprehensive snapshot yet of Bennu's history. One key discovery was the presence of large amounts of stardust—material that existed before the solar system formed.

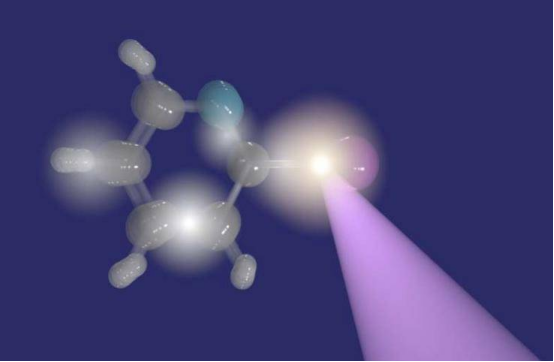

The discovery of these most ancient materials was aided in part by the NanoSIMS (nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometer) at the Kuiper-Arizona Laboratory for Astromaterials Analysis. This instrument can reveal isotopic variations (different forms of chemical elements) in samples at the nanoscale. These tiny stardust grains can be identified by their unusual isotopic compositions compared to material formed in our solar system.

Barnes said: “These are fragments of stardust from other long-dead stars that were incorporated into the gas and dust cloud from which our solar system formed.”

“Additionally, we found highly anomalous organic material that may have formed in interstellar space, and we also found solids that formed closer to the Sun—this is the first time we've proven all of these materials were present in Bennu.”

The chemical and isotopic similarities between samples from Bennu and the similar asteroid Ryugu (sampled by Japan's Hayabusa2 mission in 2019) and the most primitive meteorites found on Earth suggest their parent asteroids may have formed in a common region of the early solar system.

However, differences observed in the Bennu samples may indicate that starting materials in that region changed over time or were not as uniformly mixed as some scientists had thought.

Analysis shows that much of the material in the parent asteroid survived various chemical processes involving heat and water—even energetic collisions that led to Bennu's formation.

Yet, as reported in a second paper published in Nature Geoscience, most of the material was transformed through hydrothermal processes. In fact, the study found that minerals in the parent asteroid likely formed, dissolved, and reformed over time due to interactions with water.

“We think Bennu's parent asteroid incorporated a lot of icy material from the outer solar system, which melted over time,” said Tom Zega, director of the Kuiper-Arizona Laboratory for Astromaterials Analysis, who co-led the study with Tim McCoy, curator of meteorites at the Smithsonian Institution.

Evidence found by the team suggests that silicate minerals reacted with the resulting liquid water at relatively low temperatures of around 25°C or room temperature.

This heat may have been leftover from the parent asteroid's initial formation during accretion, or it may have been generated later by impacts, possibly related to the decay of radioactive elements deep within the asteroid. Zega believes this trapped heat may have melted ice inside the asteroid.

“Now you have liquid interacting with solid, and heat—all the ingredients for chemical reactions,” he said. “Water reacts with minerals and forms what we see today: 80% of the minerals inside contain water, and these samples formed billions of years ago when the solar system was still forming.”

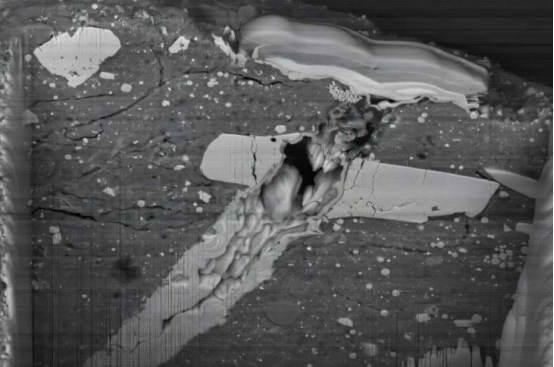

The transformation of Bennu’s material didn’t end there. A third paper, also published in Nature Geoscience, reports tiny craters and splashes of once-molten rock on the surfaces of Bennu particles—signs that the asteroid experienced micrometeoroid impacts.

These impacts, along with solar wind effects, are known as “space weathering” and occur because Bennu has no atmosphere to protect it. According to the study, led by Lindsay Keller at NASA's Johnson Space Center and Michelle Thompson at Purdue University, this weathering happens much faster than previously thought.

As remnants from the formation of planets 4.5 billion years ago, asteroids preserve the history of the solar system. But Zega notes that much of the surviving material may differ from meteorites found on Earth because different types of meteoroids (asteroid fragments) may burn up in the atmosphere and never reach the ground.

He added: “The meteorites that do reach the ground may react with Earth's atmosphere, especially if they aren't recovered quickly after falling. That's why sample-return missions like OSIRIS-REx are so critical.”