Imagine a power plant whose energy comes from the heat deep beneath our feet, providing renewable energy day and night, unaffected by weather or sunlight. Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) can harness the Earth's internal heat at extreme depths (up to 15 km and temperatures exceeding 400°C). However, traditional pumps easily fail in such harsh environments, making reliable extraction of geothermal fluids a major challenge.

An engineer focused on innovative energy technologies and his team, inspired by the oil industry, have found a new solution—gas lift technology. Geothermal fluids are located in man-made fractures deep underground under extreme heat and pressure. Current extraction methods such as electric submersible pumps (ESP) fail rapidly under these conditions. Traditional ESPs fail above 200°C, limiting access to the hottest and most valuable geothermal resources.

More than 80% of oil wells worldwide use gas lift technology, injecting compressed gas deep underground to lift liquids to the surface. However, geothermal fluids differ from oil in price and energy density, so extraction must be highly efficient to remain economically viable. The efficiency challenges that were previously overlooked in oil production have become critical in geothermal utilization.

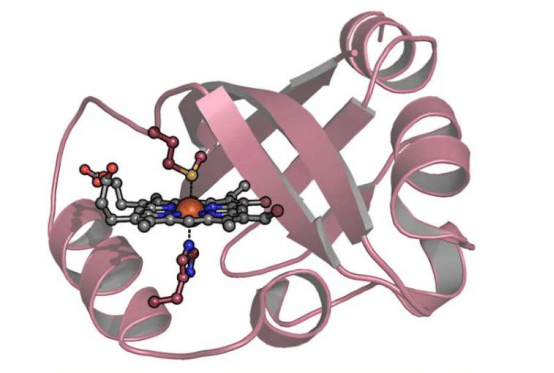

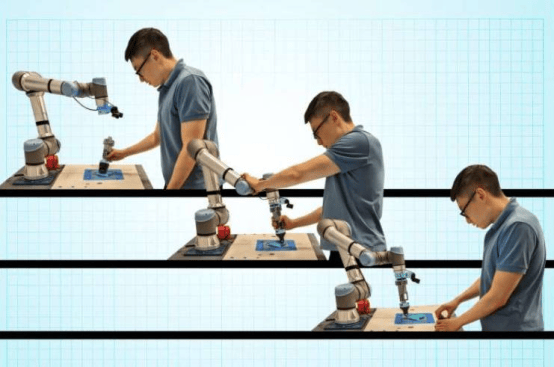

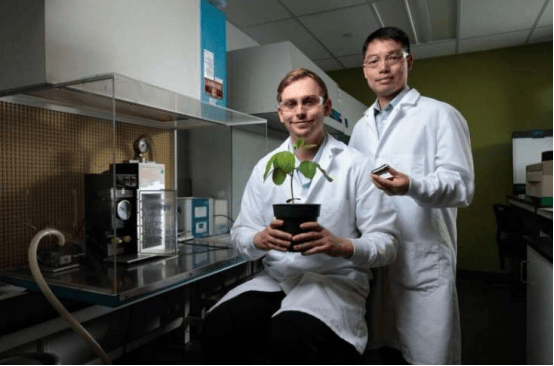

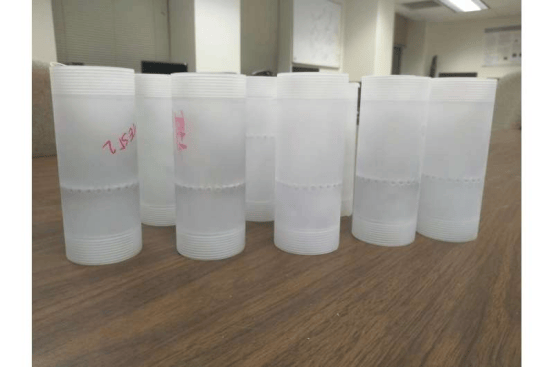

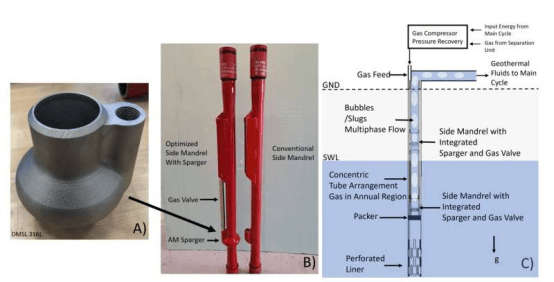

The team from the Department of Mechanical, Materials, and Aerospace Engineering at West Virginia University brought the problem into the laboratory. They designed and 3D-printed a device called a gas ejector, featuring micro-ejectors that disperse compressed gas into the geothermal fluid in the form of tiny bubbles. Through more than 100 scaled-up experiments and advanced numerical models, they determined the optimal design parameters: a distributor with 51 small holes and a carefully designed internal channel (Venturi tube) with a diameter approximately 95% of the fluid pipe diameter. The optimized distributor produces smaller, more uniform bubbles, increasing fluid extraction efficiency by about 24% compared to traditional methods without the distributor.

Small bubbles are important because they rise smoothly and efficiently, enhancing the lift provided by the injected gas. As the bubbles rise, they expand, reducing the fluid density and making it easier and more economical to pump geothermal fluids to the surface.

Real geothermal wells have harsh, mineral-rich environments that easily clog equipment. To test the robustness of the ejector design, the team deliberately blocked many of the tiny orifices. The results showed that even with a blockage rate as high as 62%, the ejector still outperformed traditional injection methods. This resilience is critical for practical deployment.

To validate the laboratory results, the team used validated numerical models to extrapolate the experimental findings to a real geothermal scenario at a depth of 4,000 feet. The results indicate that the optimized ejector could increase geothermal fluid production by an estimated 30% at the same gas injection rate, bringing hope for practical applications.

Enhanced geothermal systems hold enormous potential to provide continuous, renewable baseload power while reducing environmental impact. However, unlocking this potential hinges on overcoming technical challenges. The team is now preparing to test the optimized ejector in an operational geothermal well. A successful field demonstration would provide concrete evidence of its real-world feasibility and drive broader adoption. As the demand for renewable energy grows, such practical innovations could dramatically change how we harness the Earth's energy.