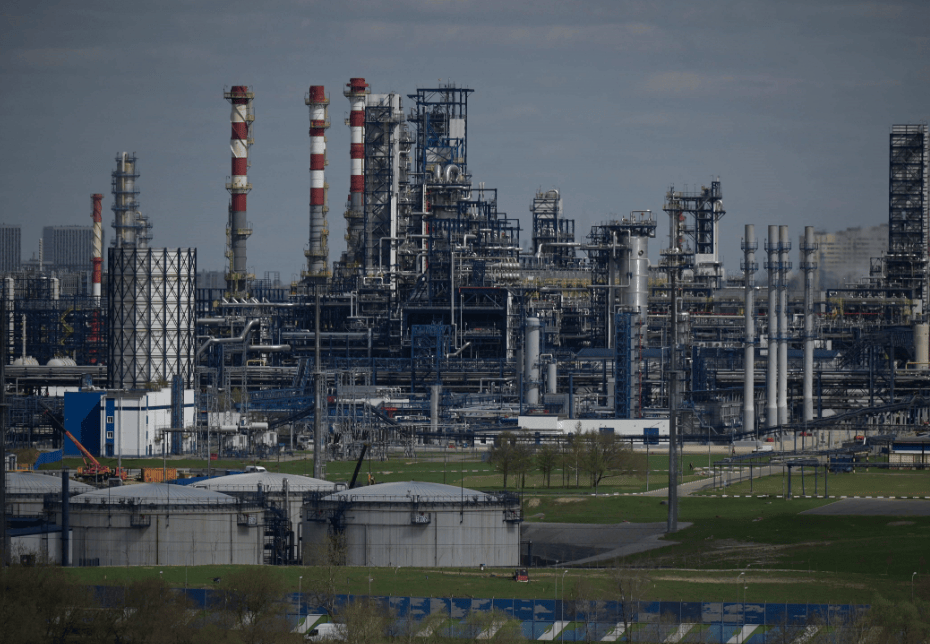

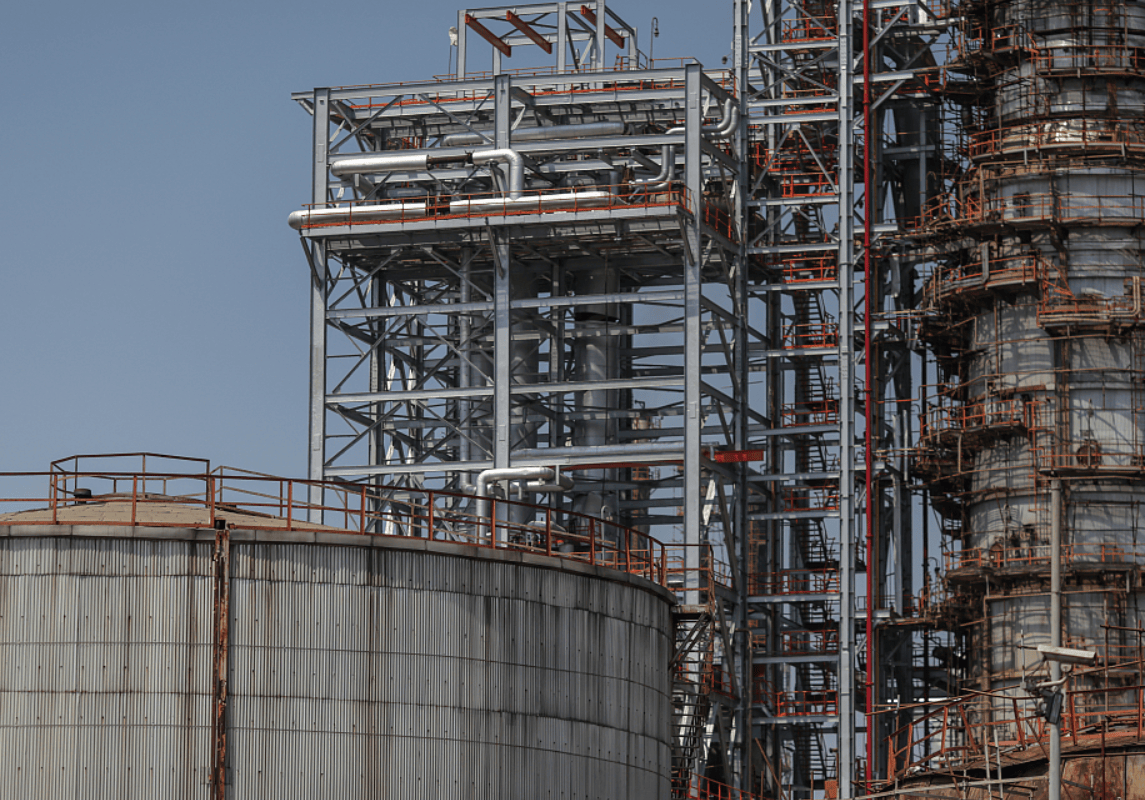

Faced with increasingly severe environmental challenges, engineers are exploring circular methods to convert industrially emitted carbon dioxide into valuable chemicals. Among these, isoprene, a key precursor for synthetic rubber, is becoming a hot target in the field of biomanufacturing. Currently, the world extracts over 800,000 tons of isoprene from petroleum annually for products like tires and adhesives, representing a market size of approximately 40-50 billion USD with continuous growth. Meanwhile, industries such as cement and energy release billions of tons of carbon dioxide each year, providing abundant raw materials for bioconversion.

Paul Dauenhauer from the University of Minnesota points out: "Isoprene is a drop-in replacement. So you can buy isoprene made from fossil fuels, or you can buy isoprene made from a renewable process, and you can't tell the difference... It's a very special molecule." Isoprene from microbial or plant sources is chemically identical to petroleum-derived products, meaning existing rubber processes require no adjustments, while the carbon source comes from waste emissions rather than fossil fuels. With global annual car production around 8 million units, rubber demand is surging. For instance, synthetic rubber consumption in India is growing 15-20% annually, driving demand for isoprene.

Industrial carbon dioxide emissions provide ample raw material for microbial isoprene production. For example, US cement plants emitted about 68 million tons of CO₂ in 2022, and coal-fired power plants emitted even more. Finland's VTT Bioruukki pilot project demonstrates the potential to capture CO₂ from industrial flue gases and convert it into products. Research Professor Juha Lehtonen stated: "If captured and converted into products, Finland could become a major producer and exporter of polymers and transport fuels made from CO₂ and hydrogen." A similar principle could be applied to isoprene production, using waste CO₂ to make rubber.

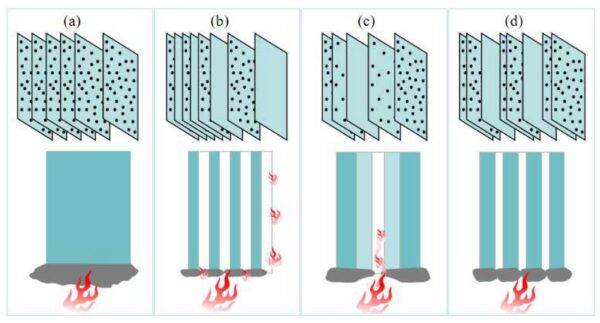

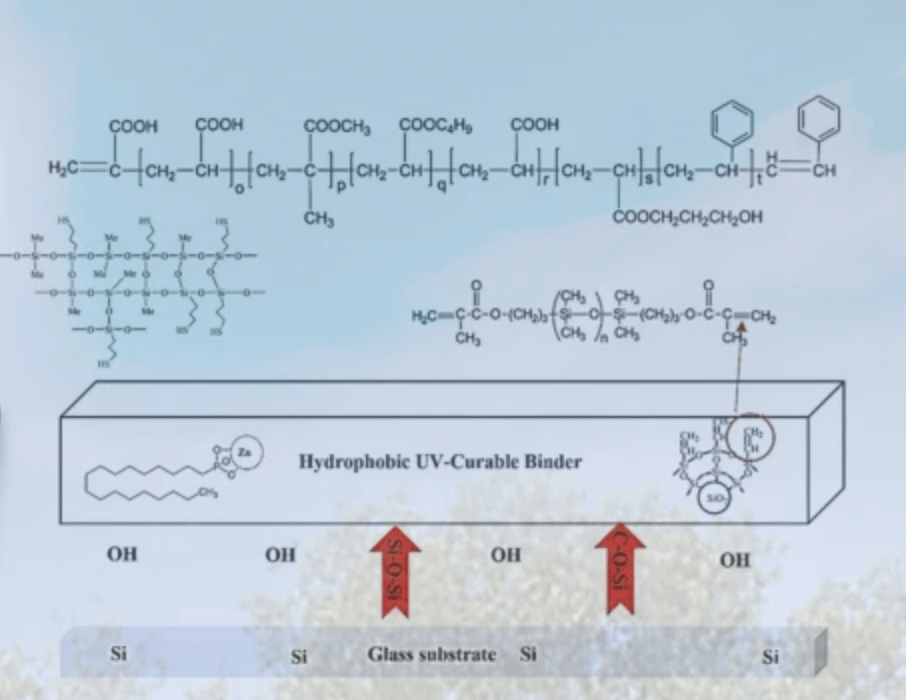

Scientists have designed various microbial pathways to convert CO₂ into isoprene. Photoautotrophs like cyanobacteria produce isoprene via the MEP and MVA pathways. For instance, Dauenhauer's team engineered cyanobacteria to achieve yields exceeding 1 gram per liter. Chemoautotrophs like methanogens can be engineered to express plant isoprene synthase, directing up to 4% of carbon flux toward isoprene in the lab. Other hosts like E. coli and yeast are also used for production, though yields are lower. Isoprene is volatile and escapes as a gas, simplifying the separation process, allowing it to be captured in condensers.

Bio-based chemicals startup Visolis is a typical case of microbial isoprene production. The company uses genetically engineered microbes to ferment wood waste into mevalonic acid, which is then converted to isoprene. Founder Deepak Dugar explains: "Our process is carbon-negative because plants pull CO₂ from the air... We process it into... synthetic rubber... most of the material... is recycled... so the CO₂ is sequestered in the material... This allows us to... not just reduce climate change, but start reversing it." Visolis has partnered with the tire industry to test carbon-negative rubber, with independent assessments suggesting its technology could reduce lifecycle emissions by over 40%.

Although engineering challenges exist, such as the need to scale up and reduce costs, bio-based isoprene projects are receiving funding globally, including from the EU's ALFAFUELS and the US Department of Energy. Dauenhauer says: "There is an opportunity here not only to address environmental issues but to create new, better products." Producing microbial isoprene from industrial CO₂ combines climate goals with market demand, promising to drive the development of carbon-negative industries. In the future, tires may be made from carbon captured from smokestacks rather than petroleum.