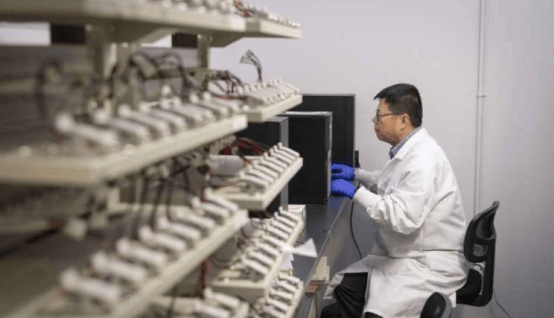

Experiments are a vital means of exploring the unknown, deepening understanding, and yielding results. Last summer, researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) conducted a tomato-growing experiment that vividly demonstrated this.

In two custom greenhouses located in a corner on the second floor of NREL's Field Test Laboratory building, the researchers cultivated a dozen tomato plants. Six plants were grown under full-spectrum sunlight as a control group, while the other six were placed in a lower-light environment, with purple panels filtering the sunlight to ensure only the spectrum most beneficial to tomatoes reached them.

This experiment aimed to validate the effectiveness of "BioMatch" technology, which allows the spectrum best suited to plant physiological needs to pass through organic semiconductor materials in solar cells. Now in its second year, the multidisciplinary project titled "No Photon Left Behind" has found that restricting the spectrum enables tomatoes to grow faster and larger than those under direct sunlight.

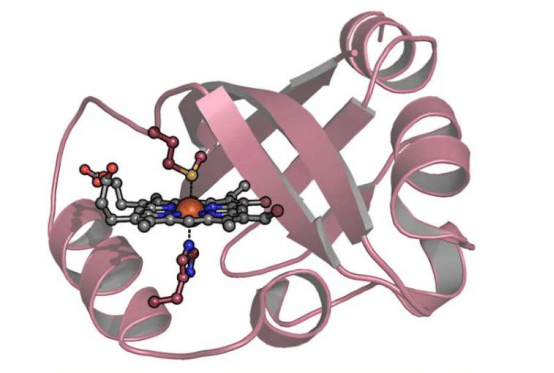

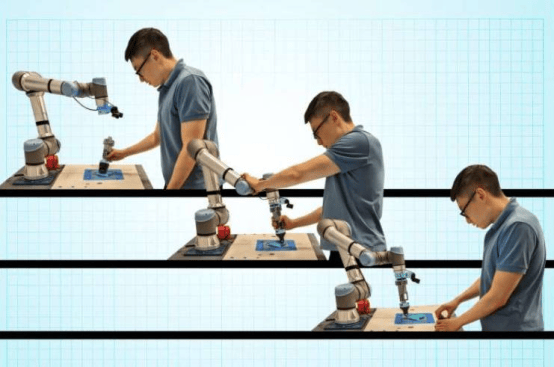

Project lead researcher and NREL organic photovoltaic (OPV) expert chemist Brian Larson explained that when light interacts with plants, it triggers different physiological pathways that determine productivity. The team studied plant responses when sunlight is filtered into the required spectrum and dosage, generating this light through the BioMatched spectral harvesting concept while using light unnecessary for plants to generate electricity via transparent OPV modules.

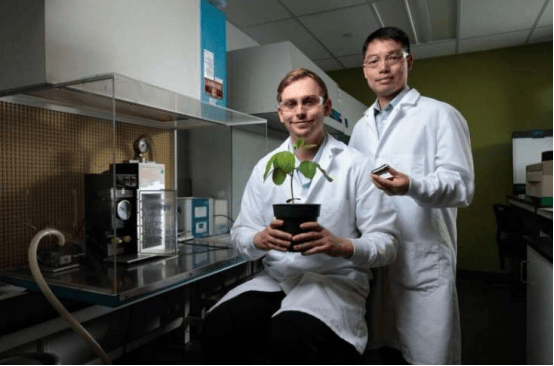

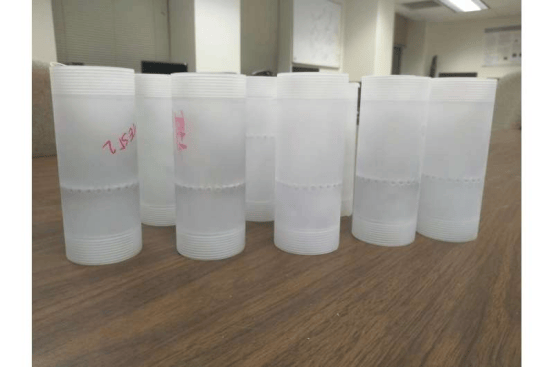

In fact, the project's initial experiments involved algae. Researchers covered bottles containing single-celled organisms with BioMatched photovoltaic filters to stimulate optimal growth, achieving significant results in just one weekend. Plant biologist and NREL algae research project co-lead Lieve Laurens stated that they demonstrated that even with most of the spectrum removed and a reduction in overall photon reception by the algae, cell growth was faster and produced more biomass.

Photovoltaic technology captures sunlight and converts it into electricity. The organic photovoltaic filters for algae and tomatoes do not generate power themselves, but the ultimate goal is to integrate BioMatched materials into semi-transparent solar panels to power greenhouses while allowing plant-usable light to pass through. Larson noted that when full-spectrum light irradiates plants, it contains both beneficial and harmful photons, requiring plants to expend energy protecting themselves from unnecessary photons. By distinguishing useful and useless wavelengths—harvesting the useless portion for electricity and leaving the rest for plant growth—a system that utilizes solar energy more efficiently can be designed.

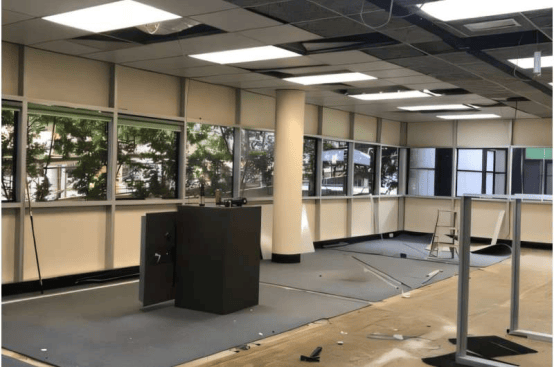

Each temporary greenhouse is approximately eight feet tall and four feet wide, with sunlight entering through wall windows and skylights. Rooftop evaporative coolers maintain air humidity, and a refrigerator on the other side of the room holds mature steak tomatoes, many the size of baseballs. Biologist Seth Starken, working with Laurens and assisted by Kelly Groves, closely monitored the tomatoes and found that those grown under OPV BioMatched Light grew taller than the full-sun treatment, despite the control group receiving 30% more light intensity. The OPV tomatoes could only selectively absorb the required solar spectrum.

Regular tests considered factors such as size, weight, and photosynthetic yield, with tomatoes grown under the BioMatched filter performing better. Starken noted that in lab experiments, these vibrant tomatoes are almost unheard of due to their small size and long life cycle, which typically make them unsuitable for laboratory use. However, they are a common variety in U.S. greenhouses, and planting them was intended to connect with real-world conditions.

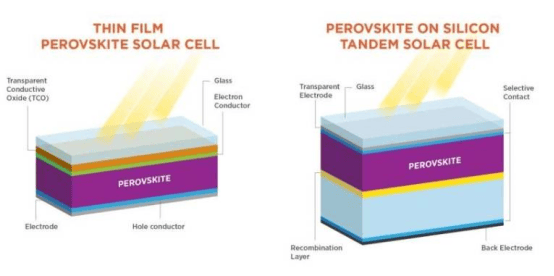

The most widely used solar cells are inorganic, made from single materials like silicon, but NREL researchers have been pioneering work in solar cells based on organic semiconductors. These are fabricated using synthetic chemistry methods and show potential for producing efficient, flexible, lightweight, and low-cost cells. Larson's database of organic semiconductor properties enabled him to select compounds that produce the correct spectrum for specific plants.

Larson said he was concerned in the ninth month of the project, as transitioning from algae experiments to tomato planting seemed too big a leap, but applying the BioMatch concept to tomatoes was "a bit like a dream come true." Growing tomatoes in the first year exceeded the project's initial plans. Confidence gained from experiments with model algal strains prompted them to advance the experiment during the summer growing season and achieve success.

This research could play a significant role in the emerging field of agrivoltaics, aiding in the design of next-generation energy-efficient greenhouses where solar panels can be customized to the ideal spectrum needed by plants.

The experimental results show that tomatoes grown under OPV grow faster, but taste testing is still needed. Larson said that given how promising these tomatoes look, he would be "personally very upset" if they ultimately turned out to have no flavor. Scientific research requires variables, so Larson purchased industry-standard greenhouse tomatoes grown organically for the testing portion. Various tomatoes were chopped and mixed, and researchers tasted and ranked them separately. The results showed store-bought tomatoes ranked last, with divided opinions on whether OPV-grown tomatoes or those under conventional light were preferred. Larson considered this a victory for Starken and the biology team.

With the preliminary experiments complete, the researchers are further deepening their understanding of the interactions between light and plant growth.