The powerful sprint of a cheetah, the graceful glide of a snake, and the dexterous grasp of a human hand all arise from the seamless interaction between soft and hard tissues—muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bones working together to provide power, precision, and range of motion for complex actions. Replicating this musculoskeletal diversity in robotics has proven extremely challenging. While 3D printing with multiple materials has previously simulated biological tissue diversity, it has been unable to continuously control key structural properties of robots, such as stiffness or load-bearing strength.

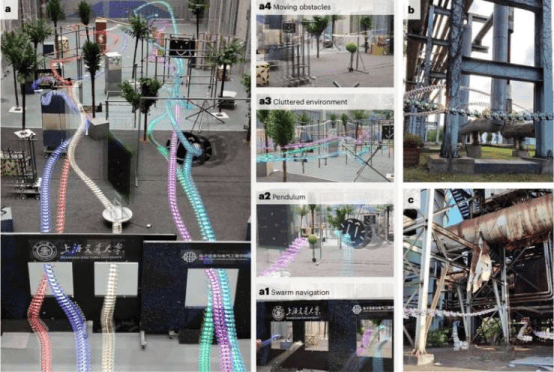

Now, a team from the Computational Robot Design & Fabrication Lab (CREATE) at EPFL's School of Engineering, led by Josie Hughes, has developed an innovative lattice structure that combines the diversity of biological tissues with robotic control and precision. The lattice is made from simple foam material and consists of multiple independent units (cells) whose shape and position can be programmed. These cells can produce over one million different configurations and can even be combined into infinite geometric variations.

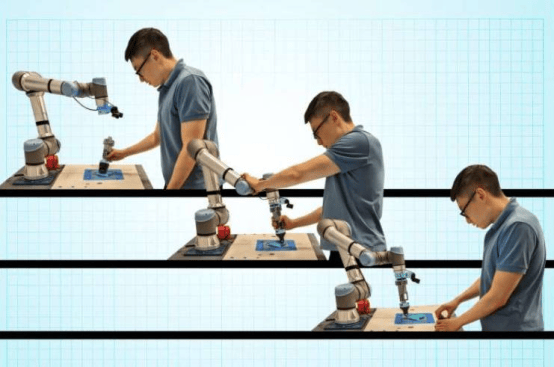

Postdoctoral researcher Guan Qinghua stated: "Using programmable lattice technology, we built a musculoskeletal-inspired elephant robot with a soft trunk capable of twisting, bending, and rotating, along with stiffer hip, knee, and ankle joints. This demonstrates that our approach offers a scalable solution for designing unprecedented lightweight and highly adaptive robots." The study was published in Science Advances.

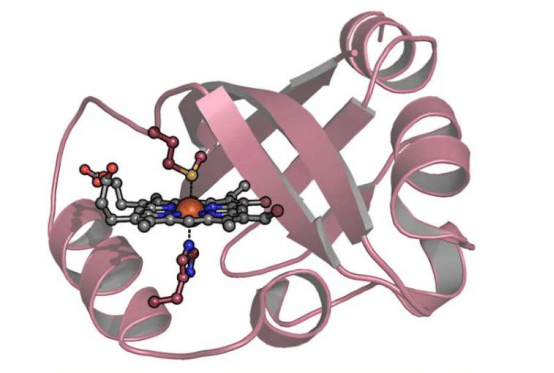

The team's programmable lattice can be printed using two main cell types with different geometries—body-centered cubic (BCC) cells and X-cube cells. When used to 3D-print robotic "tissue," each cell type produces lattices with varying stiffness, deformation, and load-bearing properties. The CREATE lab also enables printing of lattices composed of hybrid cells with shapes intermediate between BCC and X-cube. PhD student Dai Benhui explained: "This approach enables continuous spatial blending of stiffness distribution, allowing an infinite range of hybrid units—particularly suitable for replicating muscle organs like an elephant's trunk."

In addition to adjusting cell shape, the scientists can program their position within the lattice—rotating and translating them along cell axes—and even stack cells to create entirely new combinations, giving the final lattice a broader range of mechanical properties. A lattice cube containing four stacked cells can produce approximately 4 million possible configurations, while five cells exceed 75 million. For the elephant model, this dual programmability made it possible to fabricate several tissue types with distinct ranges of motion, including sliding planar joints, bending uniaxial joints, and bidirectional bending biaxial joints. The team was also able to replicate the complex movements of an elephant's muscular trunk while maintaining smooth and continuous transitions.

Hughes noted that, beyond modifying the foam material or adding new cell shapes, the unique foam lattice technology structure opens numerous possibilities for future robotics research. "Like honeycomb, the lattice offers a very high strength-to-weight ratio, enabling the creation of extremely lightweight and efficient robots. The open-cell foam structure is suitable for movement in fluids and can incorporate other materials (such as sensors) within the structure to further enhance the foam's intelligence."