When it comes to star formation, not all galaxies are alike. Some galaxies are "quenched," meaning they have run out of the gas needed to form stars and produce very few new ones. Others, like the Milky Way, are more typical, with average star-formation rates. But then there are galaxies that are extremely active, forming stars at a ferocious pace—these are known as starburst galaxies.

Starburst galaxies undergo dramatic periods of star formation, giving birth to hundreds of super star clusters containing tens of thousands or more stars each. These galaxies can form hundreds or even thousands of solar masses worth of stars per year. As a result, they are extraordinarily bright, shining in the infrared with luminosities up to trillions of times that of the Sun.

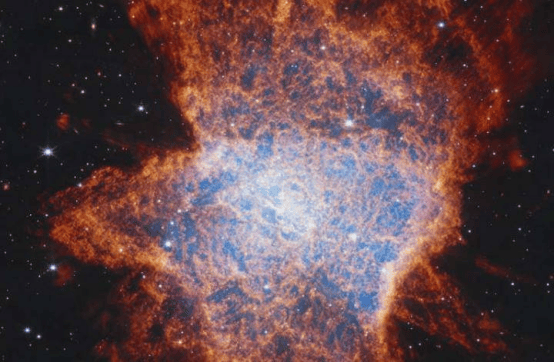

The Cigar Galaxy (M82) is one such starburst galaxy. While its extreme brightness is obscured in visible light by dust, the James Webb Space Telescope can easily observe its prolific star formation in the infrared.

The super star clusters in M82 are the primary reason for the galaxy's enhanced brightness. This super cluster contains around 100,000 stars—some clusters even rival the star counts of certain globular clusters.

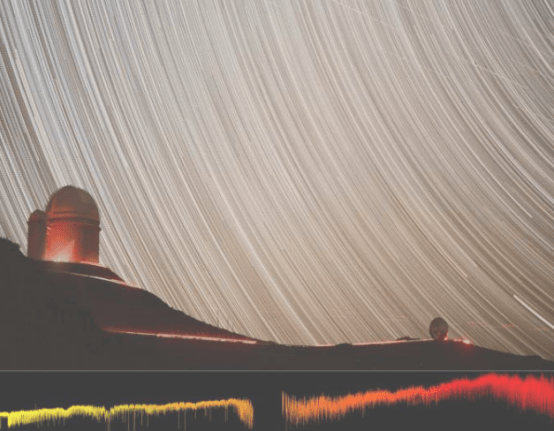

Galaxies need ample gas to become starburst galaxies, and M82 likely received a gas injection through gravitational interactions with its nearby neighbor, M81. The pair orbit each other roughly every 100 million years. These interactions have distorted M82 into its elongated cigar shape and funneled gas from its outer regions into its core, fueling its rich star formation. Astronomers are interested in M82 and its neighbor because they serve as a laboratory for observing galaxy interactions. A 2024 paper used radiation from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) to reveal a complex network of filamentary gas and bubbles produced by supernova explosions. They also uncovered M82's galactic outflows—another hallmark of starburst galaxies.

JWST's premier images also trace polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which highlight the galaxy's outflows. They appear as thin, bright streaks emanating from the galaxy's center. PAHs are important in astronomy because they have strong emission features in the mid-infrared. They are closely associated with cold molecular gas and help trace its motion.

These outflows are driven by the galaxy's abundant star-formation activity. The starburst produces thousands of stars that are hotter and more massive than the Sun. These stars generate powerful stellar winds that blow gas away. Many of them explode as supernovae, which also disperse gas. Consequently, starburst galaxies do not experience extreme star formation for more than about 100 million years before their gas supply dissipates.

M82, however, may be different. Due to repeated future gravitational interactions with M81, M82 could undergo cycles of intense star formation followed by quenching. Astronomers believe this has happened before. Roughly 600 million years ago, it went through a starburst phase, and the current one was likely triggered between 30 and 60 million years ago.

M82 is only about 12 million light-years away—quite close for a galaxy. As a result, astronomers have paid it considerable attention. Hubble and other telescopes have imaged it many times.

M82 will likely experience more starburst cycles in the future. Eventually, however, M82 and M81 will merge into a single galaxy. In the distant future, this merger will probably trigger a massive, chaotic starburst event. Ultimately, that event will also fade, and the resulting giant galaxy will settle into quiescence.