Concrete, the building material that has embodied human ingenuity and creativity since ancient civilizations—from the mud mixtures of Egyptian pyramids to the sophisticated underwater formulations of the Roman Pantheon—now stands at a crossroads of green transformation. While it has witnessed the progress of civilization, concrete is also responsible for up to 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, facing severe challenges. In the quest for sustainable construction, an interdisciplinary team from the University of Pennsylvania has provided an innovative answer.

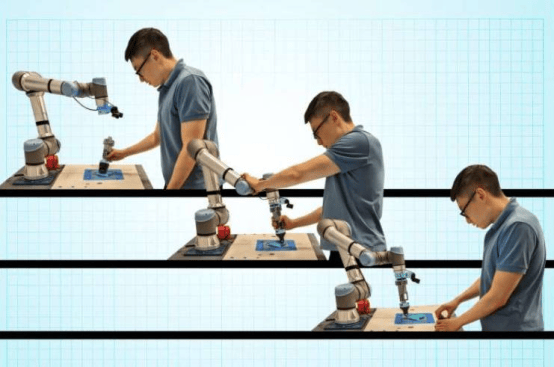

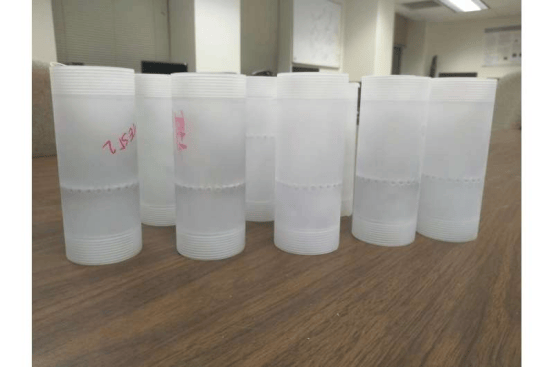

Comprising designers, materials scientists, and engineers, the team has ingeniously combined 3D printing technology with microalgae fossil structures—diatomaceous earth (DE)—to develop a bio-mineral-infused concrete. This new concrete is not only lightweight and structurally robust but also excels in carbon dioxide absorption, capturing 142% more CO₂ than traditional concrete while significantly reducing cement usage and still meeting building compressive strength standards.

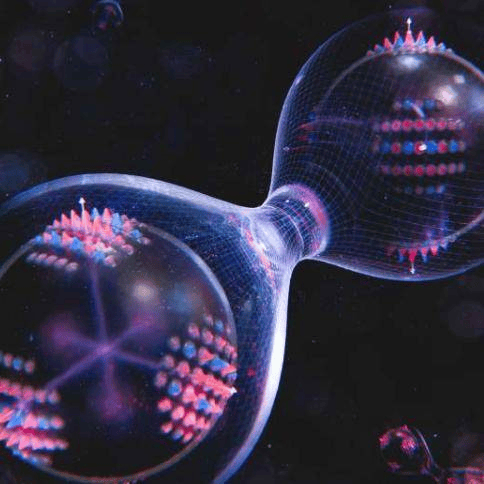

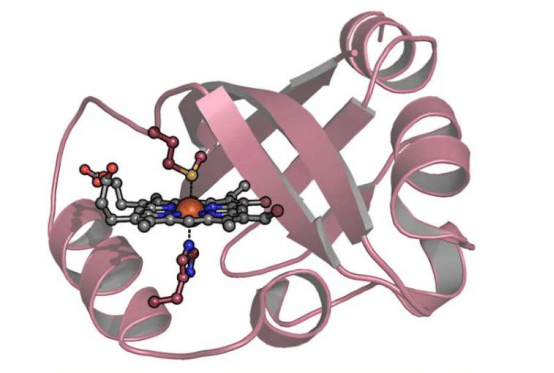

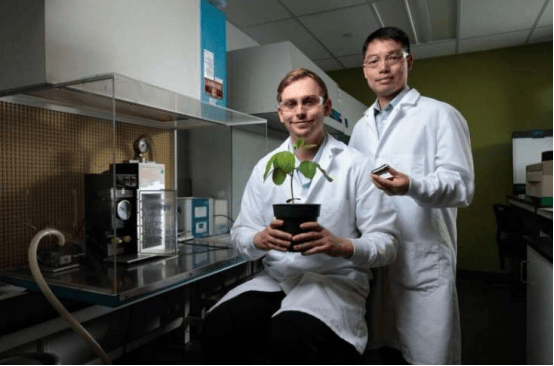

Diatomaceous earth, a material formed from microbial fossils with a delicate, sponge-like porous texture, played a critical role in the study. It not only enhanced concrete stability during 3D printing but also provided ample space for CO₂ capture. The team discovered that DE's internal pore network promotes CO₂ diffusion and calcium carbonate formation, thereby improving both mechanical performance and carbon sequestration capacity.

Published in Advanced Functional Materials, this innovation opens a new path for developing building materials that can support large structures while aiding ocean ecosystem restoration and carbon capture. Co-senior author Professor Shu Yang noted that after optimizing material geometry, the team not only significantly increased CO₂ conversion rates but also maintained compressive strength comparable to traditional concrete, achieving a dual improvement in performance and aesthetics.

Masoud Akbarzadeh, Associate Professor of Architecture at the Weitzman School of Design, emphasized that this innovation goes beyond material performance enhancement—it introduces an entirely new structural logic. By reducing material usage by nearly 60% while preserving load-bearing capacity, the new concrete demonstrates the possibility of highly efficient resource utilization.

The team also deeply explored DE's carbon capture potential and drew on advanced theories such as discrete differential geometry and triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS) to design a concrete structure that remains stable even under steep overhangs. This structure not only saves 68% of material but also significantly increases the surface-area-to-volume ratio, enhancing CO₂ absorption while retaining 90% of the compressive strength of solid cubes.

Looking ahead, the team is actively advancing the development of full-scale structural elements such as floors, facades, and load-bearing slabs, while exploring potential applications in marine infrastructure. Thanks to the high porosity and ecological compatibility of DE-TPMS concrete, it is poised to become an ideal choice for structures like artificial reefs, oyster farms, and coral platforms, supporting ocean ecosystem restoration and carbon sequestration.

Furthermore, Professor Yang's team is investigating synergies between diatomaceous earth and other binder chemistries to further reduce or even completely replace cement. She stated: "When we stop viewing concrete as a static material and instead see it as one capable of dynamically responding to the environment, we open up an entirely new world of possibilities." This innovation not only brings a dawn of green transformation to the concrete industry but also contributes significantly to global sustainable development goals.