In the field of green manufacturing, a landmark breakthrough has attracted widespread attention. The ocean, as Earth's largest dynamic carbon sink, absorbs 400 million tons of carbon dioxide (CO₂) annually through continuous exchange with the atmosphere. Now, Yale University researchers have successfully developed an efficient system that converts dissolved CO₂ in seawater into clean fuels and valuable industrial raw materials, opening a new path for green energy development.

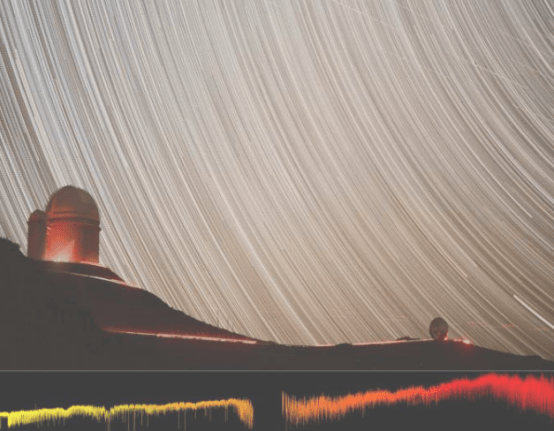

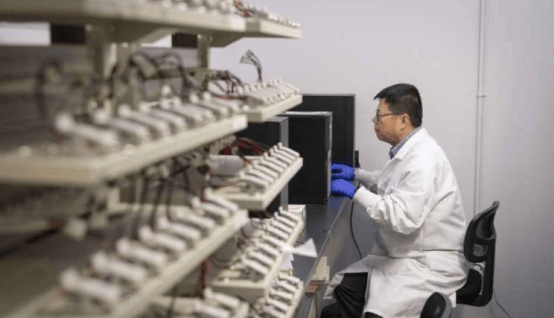

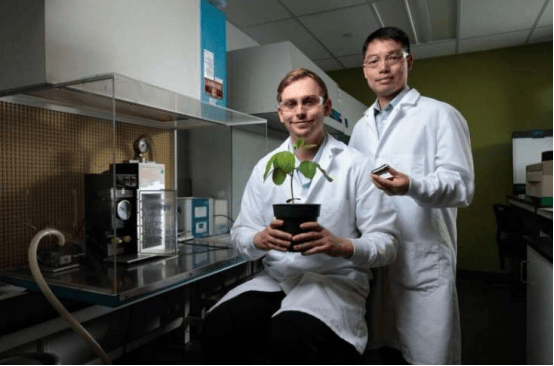

The breakthrough was published in Nature Communications. The system, led by Professor Shu Hu from Yale's Department of Chemical & Environmental Engineering and a faculty member of the Yale Energy Sciences Institute, is described by Hu as a "solar-driven, ocean-based carbon capture and conversion system"—or simply "making fuel with sunlight."

Previously, using solar energy to convert dissolved carbon in seawater into useful products faced numerous challenges. The concentration of carbonate ions in seawater is extremely low, making it difficult to simultaneously achieve high energy efficiency and selective product formation. Existing reactors were limited to laboratory-scale experiments and lacked designs capable of continuous, large-scale operation.

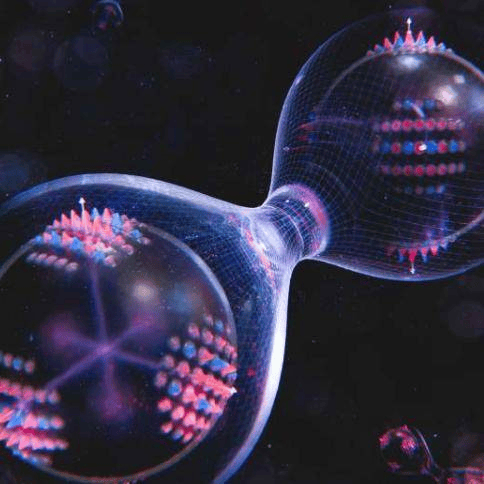

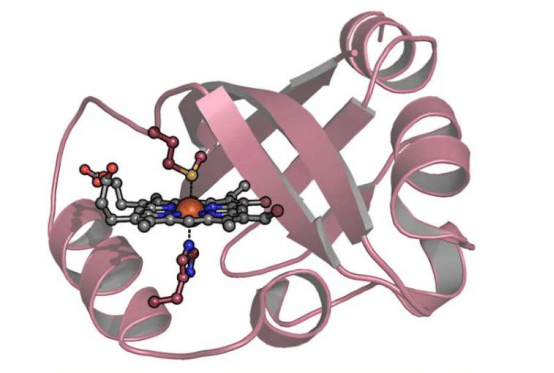

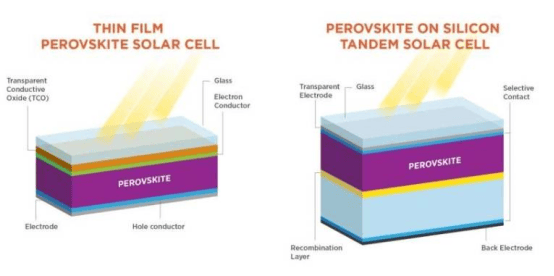

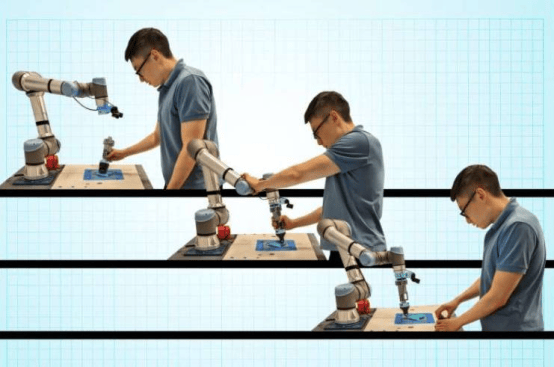

Leveraging expertise in photocatalytic design and light-driven chemical conversion reactors, the Hu team developed a novel photoelectrochemical device. Using only sunlight, the device converts dissolved carbon in seawater (primarily bicarbonate) into syngas—a versatile mixture of carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen that is a key precursor for producing high-value industrial chemicals and fuels. The process mimics photosynthesis in marine ecosystems, achieving a solar-to-fuel efficiency of 0.71%, comparable to the carbon conversion efficiency of algae.

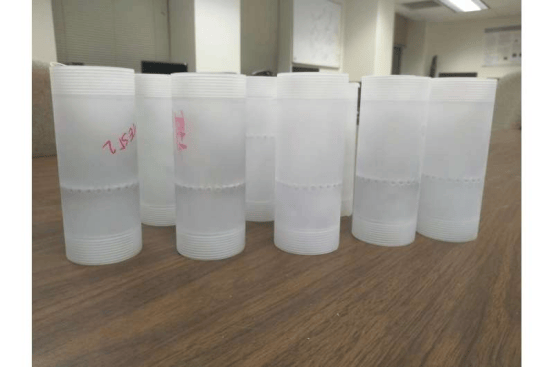

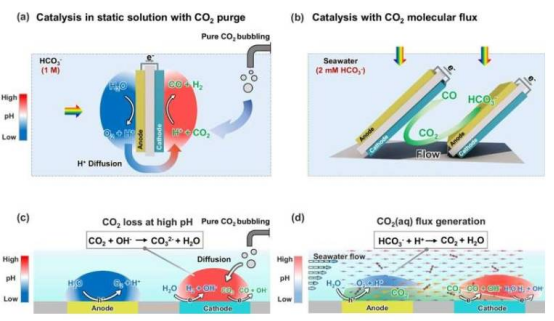

Even more strikingly, the team discovered that flow fields inside the reactor significantly affect reaction selectivity. In static seawater, CO₂ accounts for only 3% of the products; under controlled flow conditions inside the reactor, the CO₂ proportion surges to 21%. Co-author Xiang Shi, a graduate student in the Hu lab, likened it to "a perfectly synchronized relay race: the anode passes protons and CO₂ to the cathode, which completes the conversion, efficiently driving the entire reaction." By designing the reactor so water first flows through the anode (where it is oxidized to release protons), the protons trigger a series of reactions that convert bicarbonate to dissolved CO₂, which is then delivered to the downstream cathode for reduction. This regulates flux to the electrode surface, successfully removing CO₂ from seawater while harvesting fuel using sunlight.

Currently, the researchers plan to further refine the technology and scale it up into large industrial reactors. The modular reactor design allows flow cells to be assembled into square-meter-scale floating arrays. These buoyant reactors leverage natural tides and ocean currents to passively circulate seawater through the system. As seawater flows through the reactors under sunlight, dissolved CO₂ is continuously converted into syngas, which can be collected and transported to industrial facilities for chemical synthesis or fuel production. Professor Hu stated: "We hope to build large floating reactors at sea that directly use sunlight and seawater to produce solar fuels."

This innovative achievement not only provides a sustainable pathway for converting CO₂ in seawater, helping balance ocean carbon levels, but also offers a new clean energy solution for green manufacturing, potentially driving the global energy structure toward a cleaner and more sustainable future.