Water plays a critical role throughout the entire food production process—from irrigation and food processing to pre-consumption washing of fruits and vegetables. Crop and livestock growth depend entirely on water. However, once water is contaminated with pathogens, heavy metals, or chemicals, it enters the food chain and becomes a potential food safety hazard. For example, polluted irrigation water can spread pathogens such as E. coli to fruits and vegetables, and consuming them raw without proper washing can lead to severe symptoms including stomach cramps, diarrhea, nausea, and fever.

A research team from the University of Pretoria and the South African Water Research Commission has focused on bacterial pathogens in water sources for the past 20 years. With approximately 40 years of combined experience, the team has developed methods to detect water quality before and after harvesting fresh produce and identified potential pollution hotspots in the environment. Currently, the team is tracking multi-drug-resistant bacteria in South African water, assessing their impact on food safety, while analyzing the complete fresh produce supply chain and investigating pollutant cycles in vegetable production and contaminated irrigation water.

The research team points out that in rural areas of South Africa where water is scarce, collecting rooftop rainwater is a common practice. However, if water tanks are not cleaned regularly, the water can easily become contaminated with microorganisms. The slime layer in storage containers provides an ideal breeding ground for microbes. Surface water sources such as rivers and dams often contain high levels of E. coli and multi-drug-resistant bacteria, which can transfer to vegetables during irrigation. Consuming vegetables without safe cleaning poses potential health risks. However, South Africa’s current water quality guidelines do not cover multi-drug-resistant bacteria or emerging pathogens, focusing mainly on fecal indicator organisms such as E. coli.

To address these issues, the research team believes farmers, academic researchers, and government must collaborate to develop new water quality standards that reflect local conditions and emerging threats. This is essential for protecting the food system and ensuring food safety. Upstream activities, such as wastewater from failed municipal sewage systems, pollute water sources and affect downstream agricultural production when used for irrigation. Pathogens can attach to plants and survive, accumulating within one season to levels that raise concerns at the farm level. Small-scale farmers supply large amounts of fresh produce to informal markets and face major challenges in accessing clean irrigation water.

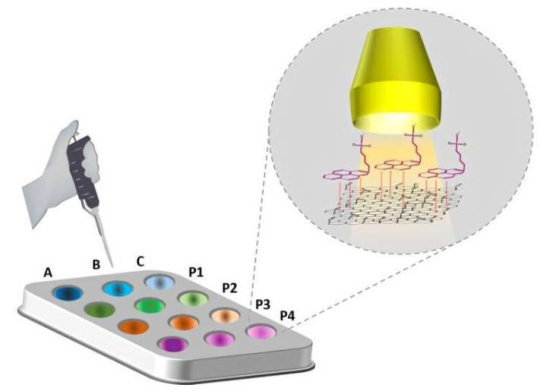

Even water that appears clean may contain hidden contaminants. To prevent this, safe water after testing and treatment must be provided, but surface water sources are often the only option for crop irrigation, livestock production, and household use in many areas, and many of these sources are already polluted by untreated or inadequately treated sewage. The study found that irrigation water from smallholder farmers transfers Salmonella and E. coli to soil and fresh produce.

Risks also exist at the retail level. Once fruits and vegetables enter informal markets, safety varies greatly depending on vendors and handling practices, such as soaking spinach in dirty water to keep it fresh. Fresh produce at sales points often carries bacterial pathogens with broad antibiotic resistance, and potentially pathogenic multi-drug-resistant bacteria are present throughout the spinach production process. Additionally, threats exist at home, where rooftop-collected rainwater contains E. coli and enterococci, which may transfer to vegetables irrigated from water tanks.

The research team emphasizes the urgent need for more real-time data and water quality guidelines tailored to specific conditions—not only showing E. coli levels but also identifying potential threats such as Salmonella and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli groups, which can cause serious illness. Currently, the team is tracking antibiotic resistance in rivers, with the goal of translating research into practical action to promote safer irrigation, improved sanitation, and reduced antibiotic resistance, protecting South Africa from food safety hazards.

In areas with known poor water quality, continuous monitoring and testing mechanisms must be established, along with monitoring and sampling of food to determine whether it is free of pathogens. Water is essential for life, and ensuring water resource safety requires joint efforts from government, scientists, farmers, and communities. Overall, South Africa needs comprehensive food safety policies and participation in implementing continental food safety agencies and frameworks to achieve more consistent regulation and control.