A team of engineers at Johns Hopkins University has developed a new, more powerful method to observe molecular vibrations, a breakthrough that could have profound implications for early disease detection.

Led by Mechanical Engineering Professor Ishan Barman, the team demonstrated for the first time how to use light to form a special hybrid state with molecules, enabling clearer and more precise detection of even the tiniest vibrations.

The research was published in Science Advances.

In healthcare, this new approach to detecting molecules could enable earlier and more accurate identification of disease biomarkers in blood, saliva, or urine. It could also have broader medical applications: in pharmaceuticals, it could monitor complex chemical reactions in real time to ensure product consistency and safety; in environmental science, it could detect trace pollutants or harmful compounds with unprecedented reliability.

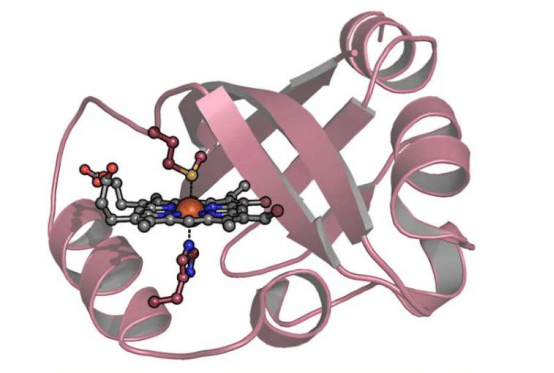

Molecular vibrations—the tiny, unique movements of atoms within molecules—provide a chemical “fingerprint” that can reveal the presence of diseases ranging from infections and metabolic disorders to cancer.

Scientists typically use techniques such as infrared and Raman spectroscopy to detect these vibrations, but these methods have fundamental limitations: the signals they rely on are often very weak, easily drowned out by background noise, and difficult to isolate in complex biological environments such as blood or tissue.

“We are trying to overcome a long-standing challenge in molecular sensing: how to make optical detection of molecules more sensitive, more robust, and more adaptable to real-world conditions?” said Barman, who holds joint appointments at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Department of Radiology and Radiological Science at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.

“Instead of incrementally improving traditional methods, we asked a more fundamental question: what if we could redesign the way light interacts with matter to create an entirely new sensing modality?”

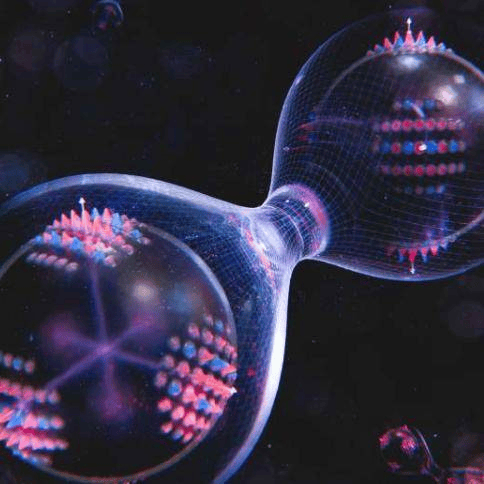

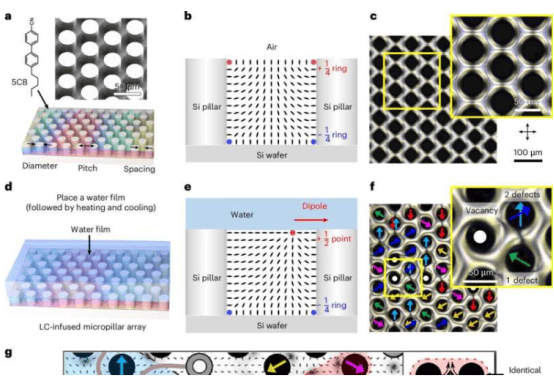

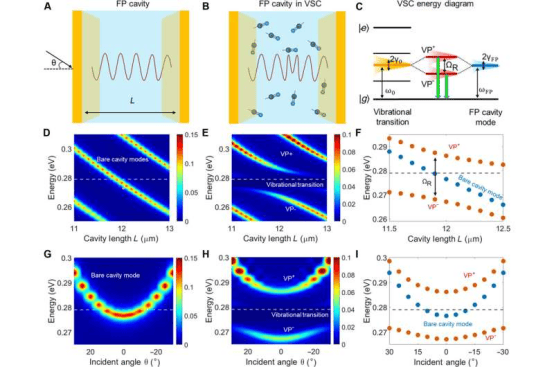

The team used highly reflective gold mirrors to form an optical cavity that traps light and causes it to bounce back and forth repeatedly, dramatically enhancing the interaction between light and the enclosed molecules. The confined light field and molecular vibrations intertwine to form a new quantum state known as a “vibrational polariton.”

The team achieved this feat in a realistic environment without the need for high vacuum, low temperatures, or other extreme conditions typically required to preserve fragile quantum states. Lead author Zheng Peng, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Johns Hopkins, explained that the study details how “quantum vibrational polariton sensing” can be transformed from concept to a workable platform, potentially giving rise to a new class of quantum optical sensors.

Zheng said: “We can now design the quantum environment around molecules, using vibrational polariton states to selectively amplify their optical fingerprints rather than passively detecting them.”

This research applies quantum principles in a novel way without traditional infrastructure, marking a significant milestone in the emerging field of environmental quantum technologies. Barman envisions ultimately designing compact, chip-scale devices that bring these quantum technologies to portable point-of-care diagnostic tools and AI-driven diagnostics.

“The future of quantum sensing is not confined to the laboratory—it will have real-world impact in medicine, biomanufacturing, and beyond,” Barman said.