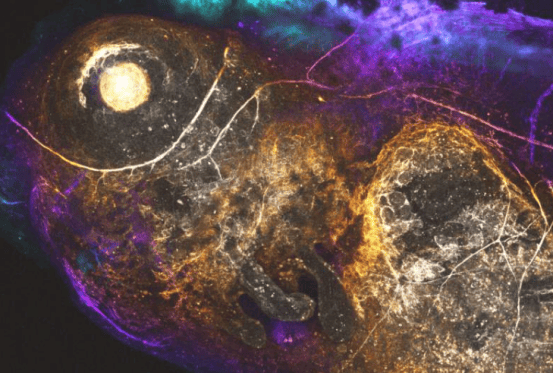

Recently, a scientific team led by the University of Rostock and the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) has achieved a major breakthrough by successfully producing liquid carbon for the first time. Previously, it was widely believed that this material could not be studied in laboratory conditions.

"This is the first time we have observed the structure of liquid carbon through experiments," said Professor Dominik Kraus, head of the Carbon Working Group at the University of Rostock and HZDR. This experiment confirms predictions from complex simulations of liquid carbon, which the team is investigating as a complex liquid form similar to water with very special structural properties.

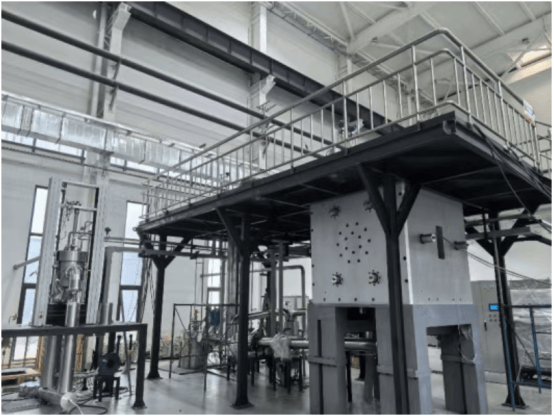

This breakthrough, utilizing the DiPOLE 100-X laser developed by the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) Central Laser Facility (CLF), holds significant implications for the future development of nuclear fusion reactors. Liquid carbon, with its extremely high melting point of about 4,500°C and unique structural properties, is seen as a key component for future fusion power plants. It can serve both as a coolant for the reactor and as a moderator to slow down neutrons, which is crucial for sustaining the chain reactions required for fusion. The researchers note that STFC's laser system has opened up entirely new research possibilities that were previously unimaginable.

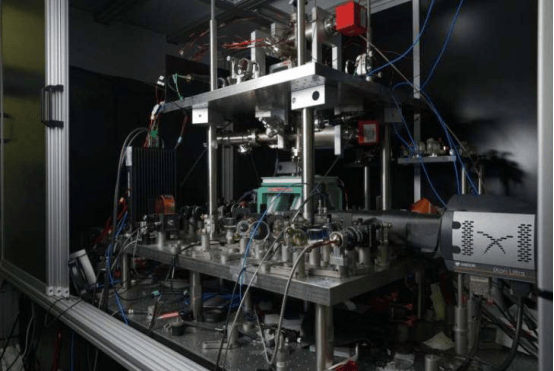

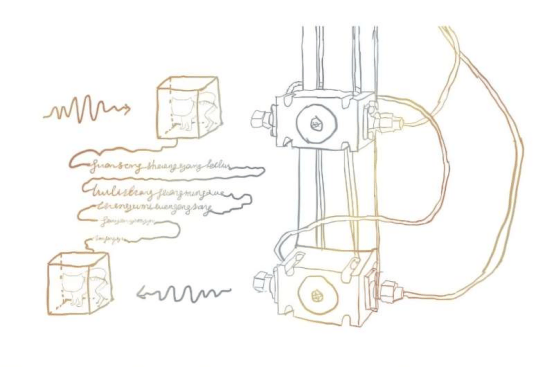

The process of generating liquid carbon is highly complex. The high-performance DiPOLE 100-X laser was used to create extreme conditions, liquefying a solid carbon sample in billionths of a second. Simultaneously, an X-ray beam captured diffraction patterns, revealing the atomic arrangement within the flowing liquid carbon. Each experiment lasted only a fraction of a second and was repeated multiple times with slight parameter variations. These "snapshots" of diffraction images were then combined to construct a complete picture of carbon's transition from solid to liquid.

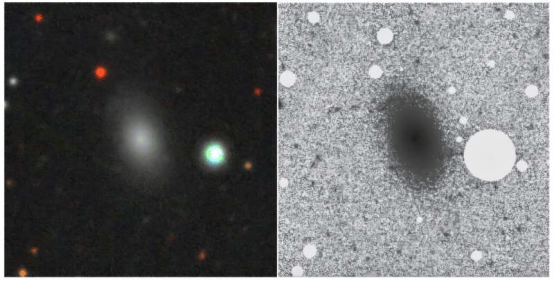

The press release points out that liquid carbon does not melt under normal pressure but immediately turns into a gas; it only becomes liquid under extreme pressure and temperatures around 4,500°C—the highest melting point of all materials. Thus, it was previously impossible to study in laboratories, and little was known about it. While laser compression provides a way to achieve this fleeting liquid state, the main challenge was making precise measurements during these brief moments. Now, the European XFEL has overcome this using the D100-X system, designed specifically for studying extreme states of materials like liquid carbon.

The scientists added that the measurement results show the liquid carbon system is similar to four nearest neighbors, much like solid diamond. Additionally, the research group precisely determined carbon's melting point, resolving long-standing discrepancies in previous theoretical predictions.

This breakthrough may advance certain nuclear fusion concepts. The press release concludes that once complex automated control and data processing systems are optimized, future results that currently require hours of experimental time could be obtained in just seconds. The research team has published their findings in Nature.