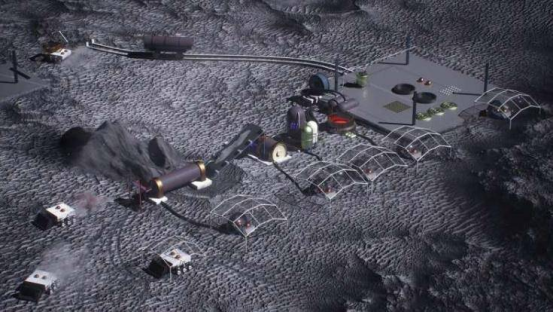

Building structures on the Moon is a challenge we have yet to fully master. Many projects have laid out grand plans, from turning lunar regolith into bricks with blood, sweat, and tears, to constructing towers for wirelessly transmitting power between remote locations. However, these projects largely overlook one of the most important materials we commonly use on Earth—ceramics.

Dr. Alex Ellery, a professor of engineering at Carleton University in Ottawa, has published a new paper on a preprint server exploring why ceramics are so vital to lunar economic development and highlighting the need for further advancements in materials science to manufacture and utilize ceramics on the lunar surface.

Lunar in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) efforts primarily focus on two areas: harnessing water ice hidden in permanently shadowed regions (especially at the lunar South Pole) and using basic regolith as a construction material for infrastructure needs like shelters or landing pads. Other resource recovery efforts aim to mine regolith or other structures as part of a lunar economy, with a particular emphasis on shipping these resources back into space for building solar power satellites or large space habitats.

While water itself has practical properties and is crucial for future human settlement on the Moon, ordinary regolith has limited functionality due to its material characteristics. Although suitable as a basic building material, it lacks key physical properties such as thermal resistance, electrical resistivity, and the ability to serve as a binder (e.g., mortar).

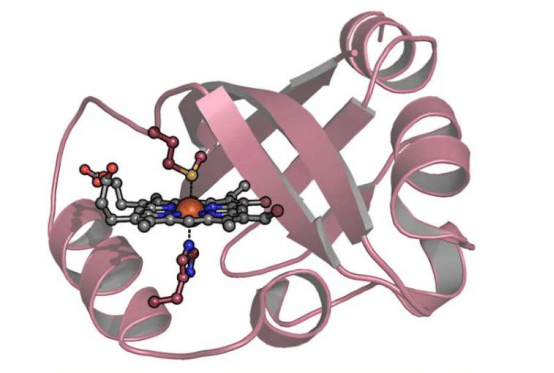

This is where ceramics come into play—many can be manufactured using the Moon's own materials. For instance, "weathering" anorthite, one of the most common materials in lunar regolith, with hydrochloric acid can produce alumina and silica, both ceramics widely used on Earth in applications requiring superior material performance compared to ordinary lunar regolith.

Additionally, Dr. Ellery describes a process for producing these ceramics using lunar highland simulants, with a byproduct of calcium chloride—a necessary component for the molten salt electrolysis reaction required to produce pure aluminum, one of the most sought-after construction metals on the Moon.

Once ceramics are produced, the next step is shaping them into useful forms. Dr. Ellery examines two different processes—traditional sintering and 3D printing. Sintering involves heating ceramics to high temperatures to bond powdered ceramic particles together, likely the most common method.

On the Moon, there is an added benefit: the process could potentially be driven solely by concentrated solar power. However, this method suffers from issues of brittleness and cracking, rendering many components made with this technique unfit for their intended purposes. Adding iron (abundant on the lunar surface) to the mixture could potentially improve the material, but this requires additional processing steps and different materials.

3D printing, on the other hand, faces its own challenges. While ceramics of various shapes and structures can be produced on Earth, most 3D printing techniques require a polymer-based binder. Since polymers are carbon-based and carbon is relatively scarce on the Moon, Dr. Ellery refers to this as the "polymer problem," which could pose a significant obstacle to 3D printing ceramics on the Moon.

He proposes several workarounds, such as creating geopolymers from clay-like lunar materials or using silicon-based polymers with lower carbon consumption. Ultimately, collecting and utilizing carbon to assist in manufacturing ceramic products is a critical pathway that requires further research.

In the end, this call to action appears to be one of the paper's primary goals. Dr. Ellery points out a general lack of understanding, from both a technical and resource allocation perspective, of the processes needed to fully utilize lunar raw materials and energy to manufacture these key materials. He argues that until we can achieve this, there will never be a fully mature lunar economy. Even if his view has only a slight chance of being correct, the issue seems worth devoting more time to solving.

More information: Alex Ellery, Ceramics – The Forgotten but Essential Element of a Lunar Circular Economy (2025).