Meet "Bille", the world's first monostatic tetrahedron: no matter its starting position, it always ends up resting on the same face. This breakthrough in geometry and engineering has solved a nearly 60-year-old mathematical puzzle and may inspire self-righting spacecraft designs for future lunar and planetary missions.

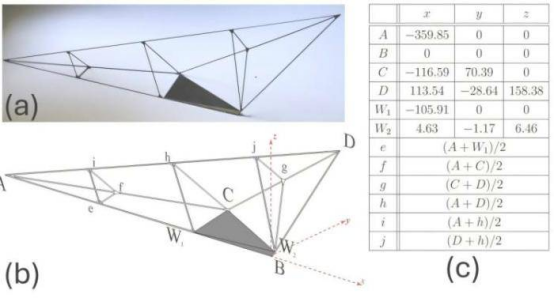

In 1966, British mathematicians John Horton Conway and Richard Guy hypothesized the existence of a homogeneous tetrahedron made of uniform material that would always flip onto one stable face, but they could not prove it. The mystery remained unsolved until three years ago, when Professor Gábor Domokos and architecture student Gergő Almádi from Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME) began tackling the problem. Using powerful computational models, they established a theoretical framework and discovered that a monostatic tetrahedron that always lands on a stable face essentially needs to be hollow, with one face thousands of times denser than the others.

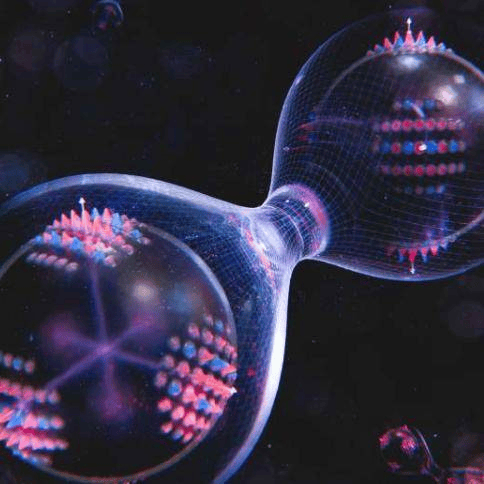

Working with a Hungarian precision engineering company, they then fabricated the first physical monostatic tetrahedron. The model, nicknamed "Bille", has a lightweight carbon-fiber tube frame, one face made of high-density tungsten carbide alloy, measures 50cm on its longest edge, and weighs 120g. It was unveiled at a BME conference, with full details published on the arXiv preprint server. No matter which face it starts on, it always ends up resting on the D-face.

The research has potential applications in improving lunar lander designs. Previous missions have been prematurely terminated when landers tipped over and could not self-right, such as the Athena spacecraft in this year's IM-2 lunar mission, which flipped and fell into a crater. Domokos and Almádi hope their work will provide valuable reference for such designs and, beyond space exploration, offer insights for self-righting objects like legged robots.