A new study published in Nature indicates that despite farmers' active adaptation to climate change, the global food system still faces escalating risks.

Contrary to previous views that warming might increase global food production, this research shows that for every 1°C rise in global average temperature, per capita daily food production worldwide will decline by 120 calories—equivalent to 4.4% of current daily consumption. Solomon Hsiang, Professor of Environmental Social Sciences at Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and senior author of the study, stated that declining global yields will harm consumers, with rising prices making food access and family support more difficult. If warming reaches 3°C, it would be as if every person on Earth skipped breakfast—a costly burden for the over 800 million people facing food insecurity.

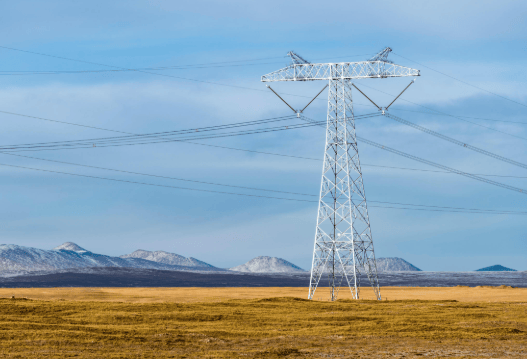

U.S. agriculture is projected to suffer particularly severe losses. Andrew Hultgren, Assistant Professor of Agricultural and Consumer Economics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and lead author, noted that the Midwest—currently ideal for corn and soy—will be devastated under high-warming scenarios, raising doubts about whether the Corn Belt will remain the Corn Belt.

Over the past eight years, Hsiang, Hultgren, and more than a dozen scholars conducted analyses at the Climate Impact Lab, co-led by Hsiang, University of Chicago economist Michael Greenstone, Rutgers climate scientist Robert Kopp, and Rhodium Group climate policy expert Trevor Houser. Hsiang warned that delaying emissions reductions would shift U.S. agricultural profits overseas, with producers in Canada, Russia, and China emerging as winners.

The study draws on observations from over 12,000 regions in 55 countries, analyzing adaptation costs and yields for crops like wheat and corn that supply two-thirds of human calories. Unlike prior studies that inadequately accounted for real-world farmer adaptations, this research systematically measured responses such as changing crop varieties and adjusting planting/harvest dates. The team estimates that if emissions continue rising, these adaptations will offset only about one-third of climate-related losses by 2100, with the rest persisting. The hardest-hit regions are modern breadbaskets and subsistence farming communities, with wealthiest areas facing average yield losses of 41% and lowest-income regions 28% by 2100.

Models show a 50% chance of increased global rice yields with warming, but a 70%–90% likelihood of decline for other major crops by century's end. Earth's temperature is already ~1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, with farmers experiencing longer droughts, untimely heatwaves, and unstable weather affecting yields.

Simulations of future crop yields under varying warming and adaptation scenarios estimate that by 2100, global crop production will fall 11% if emissions rapidly reach net zero, or 24% if unchecked. In the near term, by 2050, climate change will reduce global crop yields by 8% regardless of emissions path, due to persistent CO₂ in the atmosphere.

To help policymakers target resources, Hsiang, Hultgren, and colleagues are collaborating with the UN Development Programme to disseminate new climate risk insights to governments worldwide and develop systems identifying communities at highest risk of yield declines and eligible for targeted support. Hsiang emphasized that favorable climates are critical for sustaining high-yield farmland across generations; unchecked warming will leave future generations with land that is usable but unsuitable for farming.

Other authors are affiliated with UC Berkeley, NBER, Rhodium Group, BlackRock, University of Chicago, Rutgers University, University of Minnesota, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, University of Delaware, and Fudan University.