From touch-sensitive smartphone screens to fitness wearables and wireless earphones, electronic products are increasingly integrating into our daily lives, becoming smaller, lighter, and more flexible. As demand for electronic devices grows, so does the need for more sustainable production methods.

A research team led by Associate Professor Michinao Hashimoto from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) is addressing this challenge. The team has developed a novel 3D printing method that transforms biodegradable materials into conductive structures, injecting strong sustainability elements into various electronic components.

"As 3D printing technology advances, it is no longer limited to shaping plastics," Associate Professor Hashimoto said. "It can also incorporate functionalities such as conductivity, enabling the direct fabrication of devices using sustainable materials."

In a paper titled "Extrusion Printing of Conductive Polymer Composites via Immersion Precipitation," the team explored the use of cellulose acetate—a plant-derived biodegradable plastic increasingly seen as a green alternative to synthetic polymers. However, printing with it is far from straightforward. The study was published in the journal ACS Applied Engineering Materials.

Traditional extrusion-based printing methods, such as fused deposition modeling, rely on high temperatures—which cellulose acetate cannot withstand without degrading. Other approaches like film casting lack the precision and flexibility required for digital manufacturing.

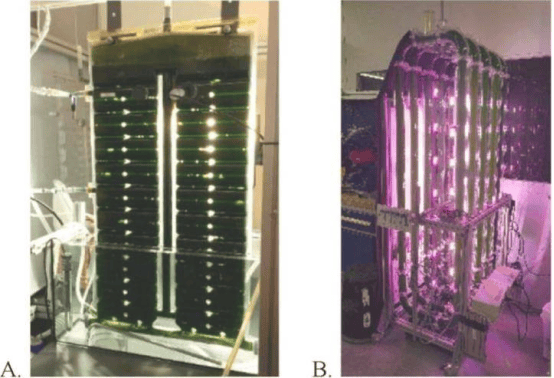

To overcome this, the researchers turned to direct ink writing, extruding polymer inks at room temperature. Their customized ink combined cellulose acetate dissolved in acetone with graphite microparticles to achieve conductivity. However, due to the slow evaporation of acetone, the ink tended to spread in air, resulting in poor print resolution.

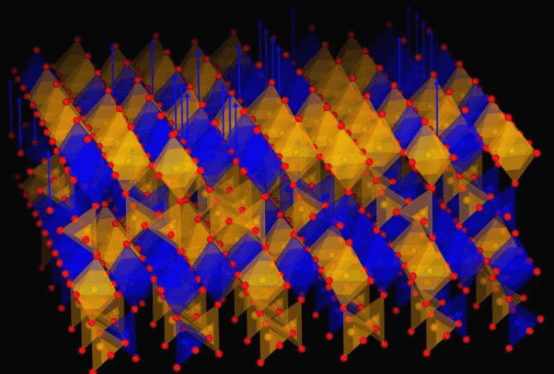

The researchers achieved a breakthrough by introducing a water medium. By extruding the ink directly into water, they initiated a process called "immersion precipitation," where water rapidly extracts acetone from the ink, causing it to solidify in place. Importantly, this process prevents material spreading, enabling the formation of sharp and clear 3D structures.

"This is the first time immersion precipitation has been combined with 3D printing to achieve conductive polymer composites," Associate Professor Hashimoto explained. "It allows us to print inks with filler contents far higher than previously possible without clogging or structural collapse."

Most printing methods struggle with conductive fillers exceeding 30% to 50% by weight. Beyond this ratio, nozzle clogging or shape control becomes problematic. However, using the immersion-based technique, the researchers were able to increase graphite concentration to 60% while maintaining good printability and uniformity. The printed composites exhibited electrical conductivity exceeding 30 S/m, sufficient for applications such as flexible circuits and soft sensors.

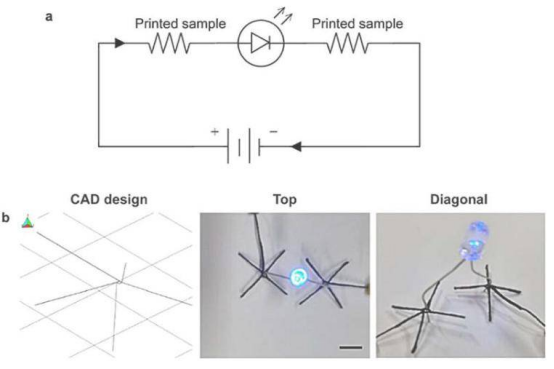

They also demonstrated how these printed composites could complete circuits, successfully powering light-emitting diodes (LEDs). To further showcase the versatility of their method, they printed overhanging helical structures into a gel-based support medium, achieving complex geometries without traditional supports or post-processing.

"Printing overhanging structures without supports, using only a gel bath, truly expands the scope of our research," said Dr. Arunraj S/O Chidambaram, the paper's lead author. "Compared to printing sacrificial structures and then removing them, this is a cleaner and more efficient approach."

Environmental sustainability is the primary driver of this project. Both cellulose acetate and graphite are biodegradable and widely available. The solvent acetone used in the ink has low toxicity and readily degrades in soil and water. By combining these materials, the team provides a viable method for electronic manufacturing that reduces environmental impact.

The team plans to apply this method to other polymer-filler combinations and test the long-term performance of their printed materials under real-world conditions. Their overall goal is to create a scalable, low-cost platform for producing sustainable high-performance devices.

Associate Professor Hashimoto added: "By tuning material properties and refining the process, we aim to build a comprehensive library of printable functional composites tailored to specific application needs—whether in wearable technology, biosensors, or flexible circuits."